Laufenberg’s Wiesbaden Ring

I think it’s probably fair to say that director Uwe Eric Laufenberg is a lot more famous than he was a year ago. His Bayreuth Parsifal, broadly centring on what one might label the possible redemption of contemporary religions, had already caused a stir long before opening night. Once it had actually opened, there was little evidence of a middle ground in terms of critical opinion: some labelled it simplistic or even outright offensive, while others hailed it as a triumph. Laufenberg himself managed to compound the controversy by weighing in with a robust attack on his critics, which included some ill-advised comments about highly regarded directorial colleagues. Nearly a year on, I’m still not entirely sure what I thought of it: my initial reaction was on the positive side, although further thought led me to wonder if I had given too much retrospective benefit of the doubt to the first two acts, after act three rather won me around. I’m therefore reserving full judgment until a second viewing. In any case, like it or nay, I thought there was evidence of a director trying to draw ideas out of Wagner’s work, and so the prospect of his full Ring cycle in Wiesbaden, with a top cast to boot, was one that I was looking forward to.

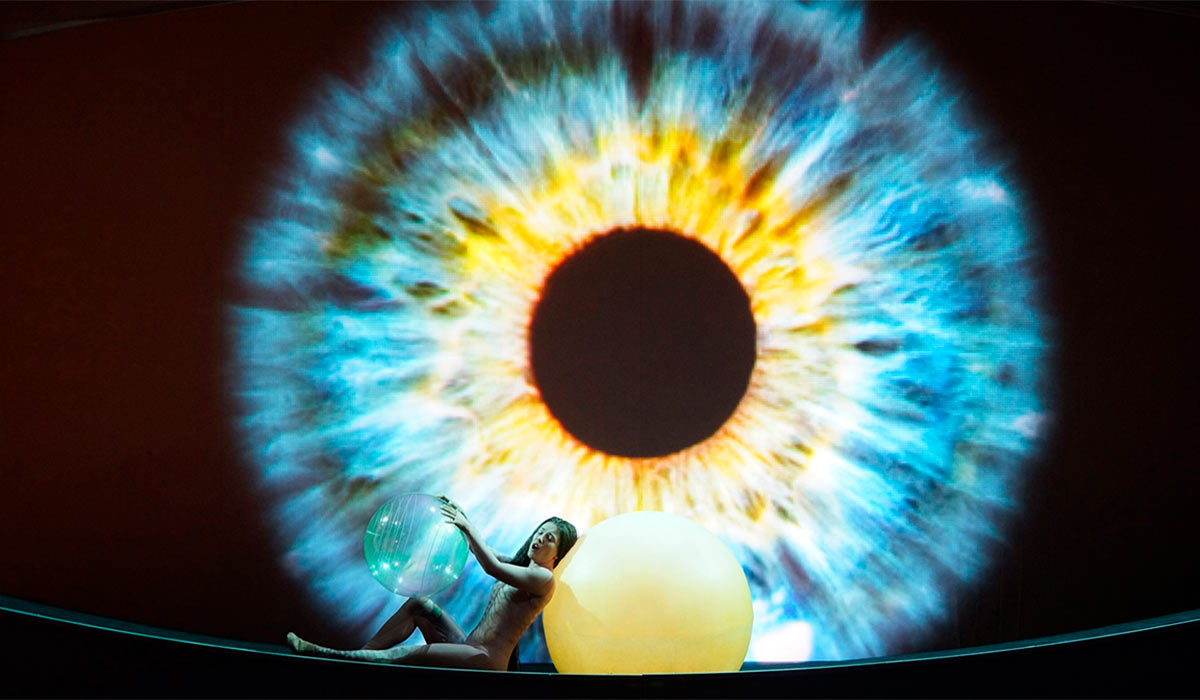

Das Rheingold began with a horizontal strip of video across the stage displaying water and the bed of a river to represent the Rhine. This was fine, if unspectacular. Following our opening orchestral journey through E flat major, the image of an eye and iris led us to the Rhinemaidens in a similar shaped room. The eye-shaped room was to return towards the end of the cycle and I remain unsure as to what it represented. Was it simply us looking in on the action? Perhaps, but maybe it was more: after some rather stock pushing and shoving between Alberich and the Rhinemaidens, with giant bubbles being thrown around to tease him, the gold was first revealed as a ball in the centre of the eye. Was it being hinted at that gold, or capital if you like, is all that we can see?

The strip of video projection returned before the second scene, this time with clouds, before Wotan and Fricka were revealed living in a large tent, the former wearing nomadic robes, the latter in a more refined dress suggesting classical antiquity. Wooden crates were piled up around, which I initially took to simply contain belongings needed for a big house move. But given the later focus of the production on military power, the thought that they might in fact contain arms of some kind seemed probable, particularly as we hear Fricka speak of Wotan thinking only of ‘Wehr und Wall’. Either way, the impression was of the gods as wanderers, needing to set up a permanent home to consolidate their power. Another idea introduced here that would reappear somewhat throughout the cycle was that of the next generation, as Freia appeared surrounded by a group of children whom she attempted to protect. The implication appeared to be that Wotan was prepared not just to sacrifice his sister-in-law for Valhalla – the seat of his power - but also the fate of his heirs too. Before the ring had even become a talking point, amour propre and selfishness were therefore already on display.

It was not long though, before we saw that Wotan was not the only character willing to forego the lives of children for his own ends. Having descended into Nibelheim – here a mine – we saw that many of the Nibelungen workers, anonymous through facial coverings, were also children, and Alberich was now in the smart overcoat of a successful nineteenth century mine owner. It was here too that we got our first hints of the production linking to the present day, for when Alberich donned the Tarnhelm, video images of Donald Trump were interspersed with those of a dragon. Subtle? Perhaps not. But links between contemporary power, war, and greed began to come into focus. The rest of the opera was played relatively straight, with the stand-out moment being the real affection Fasolt had for Freia, which was later returned after his death when she knelt over his body.

Die Walküre opened in a bar representing Hunding’s house, while Sieglinde and three other women who seemed to be working there were all dressed in a manner reminiscent of the peasant women in Jean-Francois Millet’s ‘The Gleaners’. Characterisation was handled well by the three principles, with Hunding’s brutality, and the playfulness between Siegmund and Sieglinde as they grew closer, nice touches. The occasional appearance of Brünnhilde watching the Wälsungen from above also served to introduce her to us in her role as Wotan’s Will. But aside from that, I found the production too passive in this act, content to let the singers take over, and leaving the development of previous ideas on the back burner.

Act II was more interesting from a staging perspective, although the direction continued with a softly-softly approach, triggering thoughts through general setting and costuming, and then mostly leaving us to ponder them for the rest of the act. The overall picture was, however, clear enough: the gods had progressed since Das Rheingold, in terms of power and money, and the passage of time had moved on. Wotan now appeared as an early-to-mid-twentieth century general of some sort, in grey-blue trench coat, seemingly organising the latest battle over a grand table in the war room. Fricka meanwhile was again more lavishly dressed than her husband, this time in an expensive-looking evening gown. Up until this point then, it would seem as if the pair had got what they wanted, but if Wotan had thought the building of Valhalla would entrench his military might more permanently, then the fact that this scene took place in another tent outside offered the idea that the cornerstone might not have been laid in an ideal manner. Brünnhilde, dressed like Biggles, was clearly the apple of Wotan’s remaining eye, with the hugs between them contrasting nicely with the formal relationship he had with Fricka. But her ace fighter gear couldn’t help but make one think that her place in his affections might just be based on the number of people she could shoot down, a love of power more than the power of love.

Snow began to fall before scene three, as the white tarpaulin making up Wotan’s HQ was removed to leave only the metal frame, perhaps another allusion to a lack of substance beneath his veneer of power. Then came the opera’s most direct reference back to an idea from Das Rheingold, when a child preceded Sieglinde on stage running scared from Hunding’s men, and later turned to her for protection. It was welcome to see some follow-up to what was suggested about the callousness of power games towards future generations, and interesting that it was Freia and Sieglinde chosen as the protectors, as both characters lack desire for power, and indeed are somewhat at the mercy of others’ machinations in this area. It was a bit of a shame then that this was the cycle’s last such explicit use of children to develop this issue. In any case, the second act concluded with Fricka watching over Siegmund’s death, at first looking as if she were there to gloat, but then shaking her head in despair as Wotan ran off stage in anger.

I wasn’t a fan of the staging of the Walkürenritt. Such is the fame of the music, I believe it is all the more important a production should guard against it seeming like a standalone showpiece, whereas this did the opposite by introducing a horse into the proceedings. I don’t doubt that horses can seem majestic, grand, and mighty in the right setting – one only has to think of Jacques-Louis David’s ’Napoleon Crossing the Alps’ - but in the confines of an opera house, a horse cantering around in a circle at a sedate pace gave the distinct impression we were in Barnum and Bailey’s Big Top, an impression reinforced when a section of the audience broke out into a spontaneous round of applause for the horse, right in the middle of the ‘Hojotohos’. Setting aside our four-legged friend, the staging also involved the Valkyries dragging corpses into the room, playing with them like toys, and then throwing severed arms and heads to each other. I assume the intention was to double down on the lack of human empathy in warfare, but the obviously fake limbs made it seem ironic. This might work for Frank Castorf, but in a production that otherwise took a different tone, it felt out of place. The horse gimmick also meant that the surrounding set for the entire act was a stable, which seemed to serve no other purpose in the drama.

However, all was not lost, as perhaps the most interesting idea of the opera was introduced when Wotan decided to put Brünnhilde ‘in festen Schlaf’. Here, the Valkyries brought in a statue of a woman with sword and shield in hand reminiscent of the Niederwalddenkmal statue of ‘Germania’ located on the bank of the Rhine. The real-life monument was built to commemorate the unification of Germany following the Franco-Prussian war, and stands as a symbol to the union of all Germans. Below the statue there are also reliefs depicting war and peace and the lyrics to the patriotic anthem ‘Die Wacht am Rhein’, in which men pledge to defend the Rhine from Germany’s enemies. That being the case, the choice to place the sleeping Brünnhilde inside the facsimile was fascinating. If she is both the agent of Wotan’s power and Germania, was this the god – still dressed in early twentieth century uniform - putting his militaristic Germany to sleep, the unified country ready to be awoken once more by one freer, or who perhaps stands more for freedom, than him? With this to think on, videos of modern city traffic brought us back to the present day as fire surrounded the statue and the final music played out.

The present day, or something approximate to it, was where we picked up in Siegfried, and it was at this point that the production really took off. A shanty town intermingled with faces was our backdrop, and presumably also our broad location. In front of it stood Mime’s home, a shabby-looking flat squeezed into a junk yard of some kind, with tyres piled up high in the background. Shabby it may have been, it was nevertheless equipped with modern fittings such as a cooker, a fridge, a television, and a couch, as well as an area to the side for his forging work. Shortly after Mime – here with a dishevelled appearance perhaps one notch short of Ratso Rizzo in ‘Midnight Cowboy’ – returned home with the groceries, a dreadlocked, hoodied Siegfried entered with the bear, or in this case, a punk he had befriended.

Almost immediately the detail in the direction of this scene stood out - in a good way - compared with the style of the previous two operas, with each of many mundane household things the two singers did helping to quickly round out their characters. Mime began to knit, while Siegfried grabbed a beer from the fridge. The fact that we were looking at an overgrown child and his put-upon uncle was made clear when Siegfried quite literally threw some toys out of a pram upon breaking the sword. Mime’s attempts to pacify the man-child with a stuffed animal then failed, and Siegfried sulked off to the couch, put on his headphones, and proceeded to play some air drums with Mime’s knitting needles. It was all done with just the right amount of humour, furthered the drama, and was busy and engaging without any hint of superfluity.

The usual questions about exactly how Mime really came to be in charge of Siegfried were raised when the dwarf produced Sieglinde’s dress for Siegfried, whose longing to know more about his mother was touched with the sadness of a lost childhood. Whatever else he would later go on to do, did he not also share something with the children we had seen in the previous two operas, whose lives would be changed by Wotan’s lust for domination?

The entrance of the Wanderer and the questions scene helped to clarify many of themes that had been hinted at up until that point. When describing the Nibelungen ‘in der Erde Tiefe’, video images of coal mines and forging reinforced the message from the third scene of Das Rheingold that these were workers under the yoke of capital. For the giants of Riesenheim, container shipping terminals and vessels flashed on screen, as well as large skyscrapers. The business of the moyenne bourgeoisie then - capitalistic industry and trade - had won ‘den gewaltigen Hort’. Above them though lived the gods – the super-rich, and the political elite. Ferraris, private jets and yachts gave way to videos of riots and protests, before Donald Trump and Vladimir Putin appeared, and finally the explosion of bombs when the Wanderer spoke of the spear and how all obey its master. The message was now clear enough: the working and middle classes are controlled, not just by money, but by warfare orchestrated by those who direct the armies.

For the forging scene, the idea of technological progress was picked up and intermixed with what we had just considered, leading us to contemplate what and who determine success in modern warfare. Siegfried picked up an iPad from which he read instructions on how to forge Nothung, and further videos played that combined more combat with computing. The power of Nothung then could only be attained by a member of the younger generation who understands and embraces, one might say who has never felt fear of, modern technology. The scene also continued the eye for detail Laufenberg showed earlier in the act, with excellent coordination of Siegfried and Mime around the kitchen, smithy and junk yard, all the while adding nice touches to embellish characterisation, such as having Siegfried juggling at one point. The act as a whole was superb, as good an act of opera as I have seen for a long time.

Happily, Act II was nearly as strong. The Doric columns of a grand office building stood before a golden wall, with neat hedges in front of it. Guarding it was a metal gate or fence, equipped with security system and intercom. It was through the intercom that the Wanderer and an unwashed Alberich - now sleeping rough it would seem – spoke with Fafner. Siegfried again made use of his iPad to play his horn call to the Waldvogel, before turning to take on Fafner. This was no battle in the real world though: instead, the graphics of a computer game were presented to us on the wall of the lair, showing Siegfried battling a dragon like a teenager takes on a boss in the ‘Final Fantasy’ series, before ‘Victory!’ was declared in big letters. I felt this worked well, for doesn’t the world hold no fear for those who treat it as one big game? And of course, it also served to further develop the notion that in the modern world, tech skills are the key to success.

The direction became more interesting still after Fafner, revealed as a capitalist boss slumped at his computer, had died. Office workers in suits came in to discover the body of their leader, and a TV crew arrived to interview Siegfried and the Waldvogel about the hostile takeover of the company. Siegfried posed for photos with the dead giant, was swiftly given a suit to wear, and received a round of applause from his new underlings as he took up the ring and Tarnhelm. Secret service types arrived to guard the new CEO, and after a quick glass of champagne to round off the celebrations, Siegfried ensconced himself at Fafner’s desk and got ready for work. Was this it? Was this ‘Victory!’ for an independent, technologically savvy, fearless man of the future? Were we being told to that young people should use their nous, leapfrog a few steps on the corporate ladder and take their place in Riesenheim? Thankfully, no. For within minutes of acquiring his new role, our hero was bored out of his brains, and ran off in pursuit of Brünnhilde. There were no more challenges for him in that world, and no fear.

We returned, as expected, to the statue of Germania for the final act of the opera, with debris now lying around it and its head broken, reminding us that all had not gone well for German unity since the years depicted in Die Walküre. Directorial nitty-gritty was however, also reduced back to the levels seen in the previous opera, making the Wanderer’s scenes with Erda and Siegfried seem a little by-the-book for my taste. However, following Wotan’s defeat, a stream of binary numbers descended over the stage as Siegfried braved the fires, his iPad continuing to prove his real sword. And with Brünnhilde freed from the statue but now in civilian clothing – Germania with neither breastplate nor helm – we had a fitting conclusion of a united Germany freed from historical associations with warfare, and reborn, through freedom, love, and progress. At least for the moment…

Where would Götterdämmerung take us then? Further forward into the future? Back around to the beginning again? And how would it bring together the various ideas from the previous three evenings regarding, time, war, money and technology?

The prologue began well enough, and seemed to place us somewhere in a time yet to come, as the Norns used Harry Kupfer-esque green lasers to spin their rope whilst surrounding a modern, glass-walled house with a fire burning inside. As the lights came up, our newly domesticated couple entered, Siegfried with a cup of coffee and a razor, hair now short and neat, and Brünnhilde following in a dressing gown. On display was the broken head of Germania, seemingly both their trophy, and relic of a past they had helped usher away.

Given this start, which was promising if not at the directorial heights of the first two acts of Siegfried, the first act proper was a big disappointment from a staging perspective, with the hands-off approach returning stronger than ever and only the broadest of brush strokes used to tell us where we now were, and how it related to what had come before. The thin strip of video seen in Das Rheingold made its first appearance of the night for Siegfried’s Rheinfahrt, leading us pleasantly but unremarkably along images of the river before arriving at an industrialised port with shipping containers, presumably an indication of the values to be encountered in the hall of the Gibichungs. The hall itself was a generic grand room with black walls and red curtains, while Gunther, Gutrune and Hagen all appeared in dark costumes. Hagen’s was vaguely militaristic in a Bond villain kind of way, and all three were just quirky enough to be from the near future. The same table Wotan had been seen going through his battle plans on in Die Walküre was situated in the middle of the hall, and it was also on this table that the blood oath between Siegfried and Gunther was taken, complete with a signing of contracts. This invited comparison between the two sets of dodgy deal-makers, but the rest of the act was pretty empty in terms of the thematic progress of the production, the singers essentially left to get on with it. Hagen’s Watch was done simply with a spotlight on the character, the Waltraute scene as a straightforward argument between siblings back at our glass-walled home, and the return of Siegfried-as-Gunther done with Siegfried wearing a mask. As Bing Crosby once said, ho hum, ho ho hum.

But as was the case in Die Walküre, just at the moment I thought the production might be going totally off the boil, the most interesting idea of the opera stepped forward. During the scene with Alberich and Hagen, the former rose from a chair to reveal a series of runes on the back, which were then magnified onto a big screen. I did not quite manage to note them all down accurately enough to look up any potential message afterwards, but I believe they corresponded to the runes of the Elder Futhark, used by Germanic tribes up until about the 8th or 9th century. Now, the word ‘Rune’ is not actually mentioned in this scene, but going back a bit, we already heard the word several times in the prologue and Act I: first the Norns speak of the runes carved by Wotan in the spear to mark his treaties; next Brünnhilde tells Siegfried that she has given him what the Gods taught her, ‘heiliger Runen reichen Hort’; and then, Siegfried gives her the ring in exchange. Most interestingly of all, in Act I, Siegfried asks ’Are these [gute Runen] which I read in her eyes?’ when he first meets Gutrune. Of course, his words are a direct reference to her name, which is itself derived from the same sources as the word ‘Rune’ and might approximately mean ‘secret of the Gods’ - or in this context perhaps ‘good signs’ or ‘good omens’?

That’s all very well I hear you say, what does all this mean in the context of the production? Well, I’m not quite sure. None of the previous instances of the word being mentioned were highlighted at all, and I may be guilty of trying to read too much into it. But undoubtedly runes are associated with ancient Germany, being the language of Wotan and his those who worshipped him: was Hagen simply dreaming of taking his place? Or perhaps he was imagining ancient runes as a kind of metonym for his ideas of battle-won Germanic power. If this were the case, was there not an additional implication that as well as the curse of the ring, the transfer of this ‘old’ knowledge from Wotan, first to Brünnhilde and then to Siegfried, rather than protecting them, was actually in some way infecting the pair with a set of values from the past, propagating the world of power games and helping to doom them along with him? Had they unwittingly taken on bad omens, and was Gutrune in some way destined to separate herself from them?

Whatever the case, after this thought-provoking interlude, the production carried on much as before. The vassals arrived with black helmets and machine guns – the dystopian future setting now more clear. A variety of coloured flags were then waved to mark the arrival of Gunther and Brünnhilde, and the rest of the act played out as it does on the page.

The final act returned us to the eye shape of the opening scene of the cycle, except now it was a sleazy bar with its name ‘zum Rheingold’ flashing in neon letters, and the Rhinemaidens were now dressed in stockings and leather tops. If the eye-shaped room had previously hinted at our own tunnel vision for gold, perhaps the added decadence now signalled their own yearning for the ring was somehow corrupted through single-mindedness. For scene two, the vassals wore traditional country hunting gear – maybe a sign of this future society’s fundamentally outmoded principles – and the scene was once again played straight, through to Siegfried being stabbed in the back. A nice tableau was created for the start of his death scene, with various items belonging to earlier parts of his life – Fafner’s intercom, Mime’s fridge, an anvil, and Germania – collected on stage, before he expired on Sieglinde’s dress, a reminder that however much he had gone through, he was still at heart a lost child. I felt the theme of the impact of war on youth was something worth coming back to, and the collection of memories assembled a nice complement to the impending musical synthesis of motifs associated with the character. Both could have been developed more extensively through the funeral music, where instead we had another video sequence, this time depicting people holding candles, cloud-capped mountains, and cars driving through a tunnel towards a light. All evocative of a spirit expiring perhaps, but it could have done more to act as a culmination of that character’s journey, and less to seem like a set of images designed to pull a Puccini on us.

Brünnhilde returned for the final scene and removed the iPad Siegfried was still clutching from his hand. Was it then the combination of his new technology, mastered by him but unfocused, with a society continuing with tired ideas about power that proved such a fateful mix? It certainly seemed that way, as with spear and shield in hand, the Valkyrie once more became Wotan’s Brünnhilde – Germania – to unleash Ragnarok on this historically-informed time to come. One final video sequence showed missiles, nuclear mushroom clouds, and obliterated buildings as she sang of the end of the gods, before taking us out into space and through the iris of an eye. As the music closed, Gutrune returned alone to look at us through a telescope. Despite all that we had witnessed then, it seemed that we could see ‘gute Runen’ in our real future, if we chose to.

On the musical side of things, there was much to like about Alexander Joel’s reading of the score. Balance between the pit and the stage was almost always spot on, and his use of dynamic contrast was liberal but expertly handled throughout. His tempi were not broad, but they were certainly not throwaway fast, always allowing the score enough space to speak clearly. He tended to be at his strongest in the ‘big moments’ where he could really let fly: the descent into Nibelheim had some real menace about it, the opening storm of Die Walküre created a stabbing tension through bursts of sound, and the ‘Heil dir...’ exchanges between Siegfried and Brünnhilde were simply rapturous. However, that evidence of a cherry-on-top approach was also the downside of his reading, as there were too many passages where one felt momentum and energy drop, leading us to feel we were meandering around, grudgingly doing what was necessary to get to the next crowd-pleaser. Consequently, the sense of a grander structure, of fate guiding us towards the end was often lost. This was all the more frustrating as Joel proved that he was capable of absolutely nailing it when he led a brilliant Siegfried Act 1, driving the action through almost in one breath from the first bar until the last. In any case, despite the reservations, what a pleasure it was to listen to someone who was not afraid to inject a bit of Romanticism into the work, and to appreciate and make the most of some of the musical climaxes. Indeed, I couldn’t help but tip my metaphorical cap during the orchestral section of Wotan’s Farewell, when the music swelled through a broad rallentando, and then a Luftpause held us back from the cliff as Brünnhilde turned back, giving her father one last poignant hug in perfect synchronization with the orchestra roaring back in on E major. The Hessische Staatsorchester itself began somewhat inauspiciously with a rather tentative depiction of the Rhine, but improved greatly by the middle of the first opera and largely equipped itself well from then on, sometimes extremely well. There were occasional moments where a fuller lower string sound in exposed passages would have been nice, and there was the odd split brass note, but nothing to get worked up about. And when the orchestra did hit its stride, we got a well-blended, Romantic Wagnerian sound, with some luscious violin playing and enough power to knock you off your feet.

Whatever high points the staging and orchestral playing may have had though, the unquestionable strongest suit of this cycle was the singing, which was always at least very good, and quite often superb. First among equals in this respect was Andreas Schager, who continues to amaze, treating us not just to both Siegfrieds, but also to his Siegmund after he stepped into that role too at short notice. There is no doubt in my mind that he is currently the world’s greatest Heldentenor, and the best since Siegfried Jerusalem was in his prime. Frankly, on the strength of these performances he might not be far off being included in the all-time-ranking conversation. The power and stamina he has quickly become famous for were there in spades – I think he might still be singing his phenomenal second ‘Wälse!’ cry now - but his performances were about much more than that. His full but pleasing tone enabled him to draw us in with lyricism during passages like ‘Winterstürme’, and there were moving, tenderly sung moments at the quietest end of the spectrum too, such as when the young Siegfried asks ‘So starb meine Mutter an mir?’ Moreover, his acting was excellent, with his Siegmund overflowing with hard-edged, alpha-male energy, and the young Siegfried convincingly giving off a different, caffeine-overdose type of energy fitting for a stroppy teenager. While it was perhaps no surprise that Schager shone, his partner-in-crime during the opening acts of Siegfried, Matthäus Schmidlecher, proved a revelation as Mime. The Linz-based singer has the ideal bright and malleable voice for the role, and he gave a splendid performance in what one might call the Heinz Zednik school - characterful but not caricatured – that was nevertheless no copy. His attention to words was precise, and his skilfully acted put-upon uncle proved the perfect foil for Schager. I hope, and indeed expect, to see him soon at Bayreuth and all the other ‘major’ houses.

Due to the sad passing earlier this year of Gerd Grochowski, we heard three singers share the role of Wotan: Thomas Hall, Egils Silins, and Jukka Rasilainen, in that order. What might be lost in consistency through such role sharing can often be made up for by the chance to look at a character from different points of view. To some extent that was the case here, with all three bringing something to the role, although for me Silins was the clear best of the three. His voice was strong and full of gravitas, enabling him to project a forceful personality in the louder passages, but a quiet power was also demonstrated at times during the second-act scenes with Brünnhilde and Fricka through the simple gift of stage presence. Well-judged acting also meant that the pain caused to him by Brünnhilde’s disobedience was keenly felt. Rasilainen intrigued as the Wanderer, coming across rather jovially during the first two acts, firmly giving the impression that he thought he was very much still in control of events. I was wondering whether we would see this continue through the third act and perhaps have a Wotan full of glee at Siegfried defeating him, or else how a change of mood would be handled. In the end we got the mood change, but I thought that while his transition first to an angrier, and then more resigned character could have worked, it missed a couple of gears out along the way. His voice was clear and pleasant, but was a touch on the light side, meaning he felt slightly underpowered in the scene with Erda. Hall meanwhile sang solidly, also with a lighter touch than some in the role that I think works better for the Rheingold Wotan than the Wanderer. His acting was far from bad, although he did not quite have the same presence as either of the other two, leading Wotan to seem rather inconspicuous at times. This was especially the case when contrasted with Thomas Blondelle as Loge, who excelled with a full-on, extroverted trickster-god approach, the words thoughtfully and skilfully delivered.

Margarete Joswig’s Fricka produced some of the most beautiful sounds of the cycle, and her anger regarding Siegmund and Sieglinde was well conveyed, as was tension between her and Brünnhilde that hinted at jealousy of the latter’s place in Wotan’s affections. Sabina Cvilak showed vulnerability as Sieglinde, and a touch more confidence as Gutrune yet still underlined with enough insecurity. Her voice was bright but with no shrillness, and a radiant ‘O hehrstes Wunder!’ stood out in the memory as the pivotal moment it should be and a highlight of her performance. As Fasolt and Hunding, Albert Pesendorfer once again proved himself in the top rank of Wagner basses around at the moment. His weighty voice and imposing figure conveyed the dark arrogance of the latter, yet as the former one felt a real sense of the good within the character, with inner loneliness and genuine affection for Freia apparent. The target of Fasolt’s affections was well-taken by Betsy Horne, and Young Doo Park contrasted appropriately as his brother Fafner. Thomas de Vries gave us some warmth and richness of tone as Alberich while also capturing the Nibelung’s frustrations, while Bernadette Fodor had the full lower register needed for Erda, and also produced some fine sounds as Waltraute. Acting wise, she seemed more at home with the poise of the goddess than the desperation and worry of the Valkyrie. Shavleg Armasi ably stood in for an ailing Pesendorfer as Hagen, while Samuel Youn was a solid Gunther, acting with more nuance than I have seen from him in the past. Of the smaller roles, balance and vocal beauty from Katharina Konradi, Marta Wryk and Silvia Hauer as the Rhinemaidens were the best thing about the opening scene.

And no, I haven’t forgotten: there was also the small matter of Evelyn Herlitzius as Brünnhilde. Aside from Waltraud Meier, is there a more committed and mesmerising singing actress than her around now? If there is then please tell me where and get me a ticket. Having seen her in the past as an almost maniacal Isolde, and as a fever-pitched Elektra that was truly exhausting to watch, I was somewhat preparing myself for an end-to-end maximalist approach here. In actual fact, her characterisation was more varied, but no less compelling for it. Building the character up throughout the operas, we started with a Valkyrie with internal strength, whose justifications to Wotan in the final scene of Die Walküre were controlled and firm rather than desperate, seemingly backed by the confidence of moral conviction. Following her awakening in Siegfried, a greater openness exhibited itself variously in joy, amazement, and fear, with all three overlapping in an ‘Ewig war ich…’ that grew from gentle, vulnerable beauty to run the gamut of emotions. With the guard having been let down at the end of that opera, the sight of Siegfried with Gutrune in Götterdämmerung produced a visceral, nauseous reaction that gave way first to unrestrained rage, before finally returning to joy by the time she spoke of ‘Siegfried, mein seliger Held’ once more. Vocally, I found her performance largely just as impressive, particularly in the final opera of the cycle. Sure, there was some poetic license with vowel sounds and the odd wild note, but I really don’t think it matters. What matters most is that she has a great ability to get her voice to embody the feelings that her character is going through at that particular moment, and it is capable of beauty as well as power to match Schager. What a pairing as Tristan and Isolde those two would make…

All in all then, an enjoyable four evenings in the theatre, if not quite the revelatory experience one hopes for from a Ring cycle. At its best in Siegfried, when Laufenberg allowed himself to build upon his ideas with the details needed to fully nurture them, the production was thought provoking, witty and slick. Indeed, if we had had four nights like that, I’m sure I’d be hailing this as a classic staging. But despite a fair number of interesting premises, at other times the dramatic impetus of the production slackened through a reliance on broad-level triggers like costume and set design, meaning intellectual threads sometimes petered out, or else required a dot-to-dot master to link together again. To some extent Das Rheingold will always be expository, and so I felt this tendency was most problematic in the second and fourth operas, with Götterdämmerung in particular giving me the bear minimum to cling onto to relate back to the rest of the cycle. I do not wish to seem too negative though, because I think the production was built on a fundamentally worthy concept, and rather just lacked at times for execution. The picture of a society doomed through an obsession with conflict and the parallel opportunities and dangers of technology hanging over it, certainly feels relevant. Moreover, the musical side also often managed to elevate the experience, either making the less compelling aspects of the staging seem less like longueurs or raising the better scenes to the level of awesome. Finally, I should also like to praise the Hessische Staatstheater for making such a standard of performance so accessible. I paid 80 Euros for the entire cycle, and had a perfect view of the stage and excellent sound. Frankly, I could have paid 50 euros and sat a few rows back and it still would have been fine. That is simply value that will not be beaten anywhere, and to be applauded. I could go on, but perhaps I’d better stop now. I wouldn’t want to miss the dropping of the mother of all tweets…

Das Rheingold

Wotan – Thomas Hall

Alberich – Thomas de Vries

Loge – Thomas Blondelle

Fricka – Margarete Joswig

Freia – Betsy Horne

Fasolt – Albert Pesendorfer

Fafner – Young Doo Park

Mime – Matthäus Schmidlechner

Donner – Benjamin Russell

Froh – Aaron Cawley

Erda – Bernadett Fodor

Woglinde – Katharina Konradi

Wellgunde – Marta Wryk

Flosshilde – Silvia Hauer

Die Walküre

Wotan – Egils Silins

Siegmund – Andreas Schager

Sieglinde – Sabina Cvilak

Brünnhilde – Evelyn Herlitzius

Hunding – Albert Pesendorfer

Fricka – Margarete Joswig

Helmwige – Sarah Jones

Gerhilde – Sharon Kempton

Ortlinde – Heike Thiedmann

Waltraute – Judith Gennrich

Siegrune – Marta Wryk

Rossweiße – Anna Krawczuk

Grimgerde – Maria Rebekka Stöhr

Schwertleite – Romina Boscolo

Siegfried

Siegfried – Andreas Schager

Mime – Matthäus Schmidlechner

Der Wanderer – Jukka Rasilainen

Alberich – Thomas de Vries

Fafner – Young Doo Park

Brünnhilde – Evelyn Herlitzius

Erda – Bernadett Fodor

Waldvogel – Stella An

Woglinde – Gloria Rehm

Wellgunde – Marta Wryk

Flosshilde – Silvia Hauer

Götterdämmerung

Siegfried – Andreas Schager

Brünnhilde – Evelyn Herlitzius

Hagen – Shavleg Armasi

Gunther – Samuel Youn

Gutrune/Dritte Norn – Sabina Cvilak

Alberich – Thomas de Vries

Waltraute/Erste Norn – Bernadett Fodor

Zweite Norn – Silvia Hauer

Hessisches Staatsorchester Wiesbaden

Conductor – Alexander Joel

Director – Uwe Eric Laufenberg

Sam Goodyear

Sam Goodyear is an opera fan and Wagner enthusiast, originally from Portsmouth but now living in Germany. He read history at Peterhouse, Cambridge, and has at various times worked as a bookie, translator, trader, journalist, and TV researcher. He currently works in socially responsible investment. While very much an amateur, his interest in music has in the past led to him singing on BBC radio, and playing the trumpet in front of the queen. He attends as much Wagner both at home and abroad as time and money will permit, and he has written on Wagner for Classical Music Magazine.

Der Ring des Nibelungen: Articles and Reviews

Nila Parly on Regietheater: Visions of the Ring

The Cry of the Valkyrie: Feminism and Corporality in the Copenhagen Ring

Sam Goodyear, Bayreuth 2022: Der Ring des Nibelungen (Valentin Schwarz)

Mark Berry, Bayreuth 2022: Das Rheingold (Valentin Schwarz)

Mark Berry, Bayreuth 2022: Die Walküre (Valentin Schwarz)

Mark Berry, Bayreuth 2022: Siegfried (Valentin Schwarz)

Mark Berry, Bayreuth 2022: Götterdämmerung (Valentin Schwarz)

Mark Berry: Bayreuth 2017: Das Rheingold (Frank Castorf / Marek Janowski)

Mark Berry: Bayreuth 2017: Die Walküre (Frank Castorf / Marek Janowski)

Mark Berry: Bayreuth 2016: Das Rheingold (Frank Castorf)

Mark Berry: Bayreuth 2016: Die Walküre (Frank Castorf)

Mark Berry: Bayreuth 2016: Siegfried (Frank Castorf)

Mark Berry: Bayreuth 2016: Götterdämmerung (Frank Castorf)

Mark Berry: Bayreuth 2014: Das Rheingold (Frank Castorf)

Mark Berry: Bayreuth 2014: Die Walküre (Frank Castorf)

Mark Berry: Bayreuth 2014: Siegfried (Frank Castorf)

Mark Berry: Bayreuth 2014: Götterdämmerung (Frank Castorf)

Per-Erik Skramstad: Bayreuth 2013: There Will Be Blood: Frank Castorf Has Entered the Ring

Per-Erik Skramstad: Bayreuth 2010: Curtain Down on Tankred Dorst's Ring

Mark Berry: 2010 Cassiers Ring

Sam Goodyear: Laufenberg’s Wiesbaden Ring 2017

Jerry Floyd: Rheingold, Metropolitan 2010

Jerry Floyd: Die Walküre, Metropolitan 2010

Jerry Floyd Washington National Opera: Siegfried

Jerry Floyd Washington National Opera: Siegfried II

Jerry Floyd Washington National Opera: Götterdammerung Concert (2009)

Jerry Floyd Washington National Opera: Götterdammerung Concert (2009)

Mark Berry: Richard Wagner für Kinder – Der Ring des Nibelungen (2011)