Interview with Lisbeth Balslev

Lisbeth Balslev: You come to Bayreuth for the sake of art

The Danish dramatic soprano Lisbeth Balslev has achieved success not only on the international opera scene in the roles of Brünnhilde, Sieglinde and Isolde, she also occupies a distinguished place in the history of the Bayreuth Festival with her interpretation of Senta in Harry Kupfer’s landmark staging of The Flying Dutchman, one of the Festival’s greatest ever successes. In this interview, she shares her experiences as a Wagner singer.

Lisbeth Balslev, you have sung the great Wagner and Strauss roles, including Isolde, Brünnhilde, Elsa, and Elektra. What is your favourite role?

With so many great works, the question isn’t easy to answer, but I suppose that ultimately I would have to say Isolde. The role encompasses the whole spectrum of human emotions – and ends with one of music’s most magnificent apotheoses, the Liebestod.

Was it apparent from early on that you would emerge as a Wagner singer, or was it something that you gradually grew into as your career developed?

The leap into the Wagner universe actually came quite early when the Royal Theatre in Copenhagen in 1977 – the year following my debut – asked me to sing Senta (in Wieland Wagner’s classic staging of The Flying Dutchman). But the parts of Brünnhilde and Isolde are absolutely something you gradually grow into and only accomplish at a more mature age.

You have a special place in many Wagnerians’ hearts for your fantastic performance in one of the post-war era’s most pioneering Wagner stagings, Harry Kupfer’s Dutchman in Bayreuth (1978-85). How did Wolfgang Wagner discover you?

Bayreuth was on the look-out for a Senta who could meet Harry Kupfer’s extraordinary demands in his pioneering new staging of The Flying Dutchman. Based on my success as Senta in Copenhagen, I was encouraged in May 1977 to audition at the Festspielhaus. I arrived directly from auditions in Bern and Zurich. I was tired and asked Wolfgang Wagner if I could start with the ”Felsen” aria from Così fan tutte, so that I could get a feeling of the space and the acoustic. ”One does NOT sing Mozart here!” exclaimed Wolfgang Wagner. I suggested that I should sing Senta’s Ballad and the first part of the duet with the Dutchman in Act II – without a Dutchman. ”Yes, yes, fine,” replied Wolfgang Wagner and sat straight down in the auditorium.

When I was finished singing, Wolfgang Wagner asked if I could sing Fiordiligi’s “Felsen” aria after all. After, Wolfgang Wagner came up on the stage and said that I was, in his opinion, the Senta they were looking for, but that he would first have to speak with Harry Kupfer. I was then able to inform Wolfgang Wagner that I had worked the year before with Harry Kupfer in his new staging of Borodin’s Prince Igor in Copenhagen, which was my debut as Jaroslavna. Final confirmation of my Bayreuth engagement as Senta arrived a few days later during a holiday in Norway.

Had you seen any performances in Bayreuth before you came to sing?

No, none.

Singers such as John Tomlinson, Graham Clark and Poul Elming have all told me how great it was to sing at the Wagner Festival in Bayreuth. What was your experience?

Singing in Bayreuth is incredibly hard work for a relatively modest fee! But, nevertheless, Bayreuth is the place where everyone loves to appear, as I do, too. You come here for the sake of art. The atmosphere is quite unique, and everyone feels privileged and is eager to do their utmost. Under Wolfgang Wagner’s direction, the atmosphere is positive and filled with humour, but at the same time marked by a highly professional attitude towards the work. Furthermore, the team spirit is perhaps stronger in Bayreuth than in regular opera houses. I had the same feeling, incidentally, at the Wagner performances in the many summers in Århus after my Bayreuth residence.

Kupfer is known for having pretty clear expectations on how things should be when he comes to rehearsals. How did you find his way of leading rehearsals?

You can’t but respect a director who has such a detailed knowledge of the work and who has done his homework so thoroughly. He knows exactly what he wants to get out of the specific artists who have been engaged for his productions. At the same time, he is open and flexible and not afraid to accept suggestions from the singers. For example, in act three of Dutchman in Bayreuth during the ”chorus duel” between Daland’s sailors and the Dutchman’s sailors, I added elements drawn from my experience at a psychiatric unit during my training as a nurse.

But when you work with Harry Kupfer, the focus on dramatic expression is so deeply concentrated that you, as a singer, must also be constantly attentive to and have control over your vocal technique.

In this staging, the Dutchman exists only in Senta’s fantasy. How did you find this way of reading the work?

Letting the Dutchman exist in Senta’s fantasy was an intelligent innovation on Harry Kupfer’s side. But there isn’t one definitive way of interpreting an opera. There must be room for each director to contribute with his interpretation of the work. It was easy for me to portray Senta as Kupfer saw. He has a good understanding for the average person’s situation with the outsider, those who aren’t like all the others, especially in a small village community. And who must escape, either quite physically, or into their own fantasy world.

Bayreuth is known for unusually thorough rehearsals. Is this only for the good, or can it hinder some of the spontaneity during the performance?

I consider the unusually thorough rehearsals in Bayreuth to be for the good - all the details become deep-seated, without overcoming the spontaneity. But it is also quite true that long rehearsals don't necessarily mean success, because it is a condition that there is a constant development during the rehearsals.

What was the public’s reaction in the year of the premiere?

The singers and the musicians were cheered by the public. But not the director. Harry Kupfer wasn’t singled out but there were boos from parts of the audience. Anything else would have been a sensation when one thinks how revolutionary the staging was – and how conservative many opera fans are. Just think how Chéreau’s now famous Ring was received at the premiere.

One of the fantastic things about Bayreuth is the visitors’ enormous passion for Wagner’s work. And the endless conflict between traditionalists and modernists is given expression in the verbal “battle” after the performances with booing and bravos. What has been your experience of this conflict?

The verbal battles between the booing and the bravos are a part of the Bayreuth Festival. It is part of the game and maybe also a part of the charm? I haven’t myself been a shuttlecock between the booers and the bravoers. On the contrary, I still hear now many years later what fantastic performances people thought I gave.

You actually jumped in as Gutrune (Götterdämmerung) in Bayreuth in 1986. The staging (directed by Peter Hall) must have been a bit of a contrast to Kupfer’s "Regietheater"?

It was in many ways a contrast – not just to Kupfer’s ”Regietheater”, but also coming from a lead role to a supporting role. I’m not actually very familiar with Peter Hall’s staging. The background is that Bayreuth, at short notice, had received regrets for the role of Gutrune, and Wolfgang Wagner asked me so sincerely for help. I had just a few days’ rehearsal and commuted between Bayreuth and Tosca rehearsals in Copenhagen. The direction of the singers was insignificant and I really noticed that the whole mood wasn’t nearly as enthusiastic as during my work with Dutchman, so I’m not surprised that this Ring wasn’t a success. A traditional performance can in any event be just as wonderful as an unconventional one.

What is your attitude towards the "Regietheater" which is, among other things, characterised by the fact that the director has freedom in relation to the composer’s stage directions?

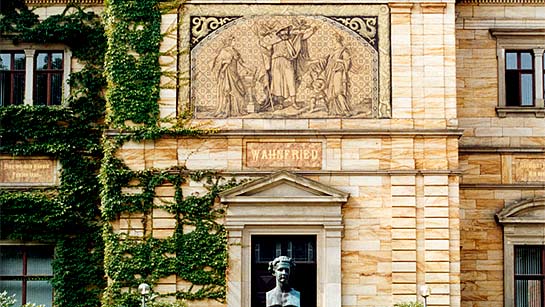

It’s necessary that opera moves with the times. People change with time, too. You get a brilliant image of this when you visit Villa Wahnfried in Bayreuth and see the scenography and photographs from the late 1800s to today. There should be room for a director to come up with new ideas, but a traditional staging can be just as good. The most important thing is that the music remains the same. Occasionally, new stagings of old works appear too thought out – as if the director, at any price, must find something new.

Villa Wahnfried in Bayreuth.

Photo: Per-Erik Skramstad

From a Wagner perspective, what do you think of the singer situation today? Good heldentenors don’t grow on trees...

In my eyes, the lack of really good tenors is particularly to blame on two things: pushing young talent too soon and the overexploitation of them. It takes time to develop a good heldentenor but these days everything has to go so fast. So, when a talented voice turns up, they are often thrown into the big heldentenor roles too soon. The performances follow too closely on each other and the voice doesn’t manage to recover.

You were originally trained as a nurse. Have you ever had use for your skills backstage?

I have fortunately not been in the situation where I needed to give heart massage or anything so dramatic. But I have, with pleasure, been able to help with good advice on the handling of minor problems. And through confidential conversations, I have been able to support colleagues who have mental problems or issues to deal with - some of a personal nature.

The Flying Dutchman on CD and DVD/Bluray

Interviews

Peter Konwitschny: I do not consider myself a representative of the Regietheater

Alexander Meier-Dörzenbach: There is so much more than mere sentimentality to this great opera

Detlef Roth: Amfortas' Suffering is Germany's

Kasper Holten: Tannhäuser's Rome narrative is perhaps all fiction—but it is his best story ever

Lisbeth Balslev: You come to Bayreuth for the sake of art

Iréne Theorin: Isolde is incredibly intense, and that really suits me

Graham Clark: I just switched hobbies

Anne Evans: At the time I hadn’t realised what a powerful impact it made

Johanna Meier on Isolde, Bayreuth and Ponnelle

Lioba Braun on Brangäne, Bayreuth and Wagner

Stephen Gould: Tristan is the end of the line

Penelope Turing: "Heil dir, Sonne!" Meant Something in those Conditions

Daniel Slater: The creation of the self through love and death

Sharon Polyak on West-Eastern Divan Orchestra, Wagner in Israel, Bayreuth

Stefan Herheim interviews

Stefan Herheim on Daniele Gatti, tempi and staging of preludes

Herheim on Parsifal: The Theatre is my Temple

Stefan Herheim links

Wagneropera.net recommends