"My Bayreuth Experience"

Travel letters and stories from Bayreuth Festival attendees.

Colin Bayliss • Clemens Bieber • Bea and Alec Bobotek • Stephen Charitan • Gary Campbell • Jerry Floyd • Sam Goodyear • Janette Griffiths • Diana Herbst • Hildegaard Arnold Kiel • Randall G. Malmstrom • Anne Midgette • Walter Meyer • Wouter de Moor • John F. Runciman • Per-Erik Skramstad • Brian Slater • Julia Thornton • Natalie Tsang • Mark Twain •

A Bayreuth Experience

Richard Wagner in Haus Wahnfried. Photo: Per-Erik Skramstad

At last, at last! After nine years of applying for tickets, my wife and I obtained tickets for Parsifal and Meistersinger at Bayreuth in 2007. I was then approaching sixty and, being a composer myself, I didn't want to die before I had heard Parsifal in the acoustic for which it was written! Although Wagner's music has never influenced my own compositions, I consider him the most profoundly moving of composers, and my collection of Wagneriana runs into hundreds of books, articles, scores, CDs of all the operas, and so on.

We determined to make the experience into something special, as indeed it should be. Therefore we flew to Cologne and traveled to Nuremberg by train down the Rhine valley. We then spent a couple of days in Nuremberg taking in the atmosphere of Hans Sachs' city.

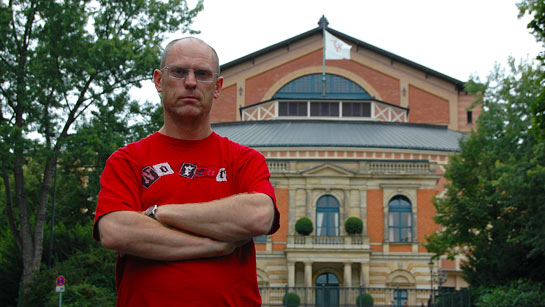

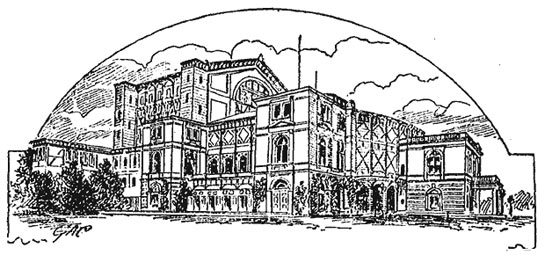

Then to Bayreuth itself! Alighting from the train, the first thing one sees is the Festspielhaus rearing out of the trees half a mile away, which is the first of many times your breath is taken away.

Our hotel was halfway between the station and Wahnfried, so after unpacking the bags, it was straight to the Wagner museum there. A small admission charge and we were in Wagner's own house with all its fascinating memorabilia. As I walked through the Saal past his library of philosophical books I burst into tears without warning. The attendant told my wife that this happens frequently.

In the evening we walked up to the Festspielhaus and talked to members of the chorus who were not singing that night. I found that my German was far better than I had thought and I could converse about other things than rings and grails!

Bayreuth Festival. Photo: Per-Erik Skramstad

The next day was Parsifal, and to enter the Festspielhaus at last was another breathtaking experience in itself. It was 80 degrees Fahrenheit inside but 90 outside, so it seemed quite comfortable! The wooden seats are also surprisingly comfortable as they support the thighs even for someone of my height of six foot three. The unique sound from the covered pit cannot be described except to say that the music seemed to be both around and within your head. It was the last of the old production of Parsifal (Christoph Schlingensief) and although the singing and conducting were near perfect, the replacement of that production can only be welcomed. So too will the replacement of Katharina Wagner's production of Meistersinger! I have no objection to the modernistic avant garde productions, but they must be done well, and this production was so misguided in concept and overburdened with so much irrelevant stage business that both the singers and the orchestra were affected. However, it did give us the opportunity to hear that wonderful acoustic in action when 1800 people booed!

![]()

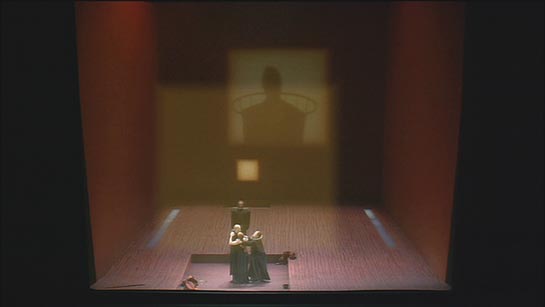

Katharina Wagner's production of Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg: Hans Sachs is kidnapped by performance artists in Act 3. Photo from 2009: Enrico Nawrath

It would be irrelevant to the Wagner theme to go into detail of the rest of our time there, but I must mention going to hear German organ recitals on instruments which are kept in immaculate tuning, unlike English ones. Also we went to a recital of English church music in Bayreuth and met someone whom I'd not seen for 15 years; then in Cologne on the way home we had dinner with a player in the Gurzenich Orchestra who surprised me by showing me a video of his conducting a piece of my music with a youth orchestra in Italy.

But back to Wagner. Let me quote Gustav Mahler. "Emerging speechless from the Festspielhaus [after hearing Parsifal in 1883], I realised that I had undergone the most soul-wrenching experience in my life, and that I would carry this experience with me for the rest of my days". It would be difficult to express the Bayreuth experience better except to say that it has been with me consciously every day since August 2007.

Colin Bayliss • Clemens Bieber • Bea and Alec Bobotek • Stephen Charitan • Gary Campbell • Jerry Floyd • Sam Goodyear • Janette Griffiths • Diana Herbst • Hildegaard Arnold Kiel • Randall G. Malmstrom • Anne Midgette • Walter Meyer • Wouter de Moor • John F. Runciman • Per-Erik Skramstad • Brian Slater • Julia Thornton • Natalie Tsang • Mark Twain •

Tenor Clemens Bieber on Bayreuth

(Interview with Mainpost.de: Clemens Bieber: Ein Würzburger für Wagner)

Seit 1987 treten Sie bei den Bayreuther Festspielen auf.

Bieber: Von 1996 bis 2000 habe ich pausiert. Seit 2001 bin ich wieder dabei. Dieses Jahr sind es also 20 Jahre. Ich bin inzwischen der dienstälteste aktive Solist in Bayreuth.

Hat Bayreuth für Sie etwas Besonderes?Bieber: Es hat eine besondere Atmosphäre. In der langen Zeit, die ich dort verbracht habe, habe ich so viele interessante Leute kennengelernt, habe so gute Produktionen mitmachen können. Man hat tolle Dirigenten, man hat sehr gute Regisseure. Die Voraussetzungen sind einfach optimal. Es macht mir eine Riesenfreude, dort zu arbeiten.

Sind Sie in Bayreuth nervöser als sonst?Bieber: Man ist immer nervös. Es relativiert sich aber.

Ich habe den Eindruck, das Publikum in Bayreuth sei kritischer als anderswo und auch besser informiert. Sie haben den Vergleich, etwa mit der New Yorker Met. Wie sehen Sie's?Bieber: Das Bayreuther Publikum ist wissender, erfahrener und oft auch sehr viel kritischer als anderswo. Wobei in Bayreuth manchmal Maßstäbe angelegt werden, die kaum zu erfüllen sind. Ich sage immer: Leute, bedenkt, dass es eine Live-Vorstellung ist! Das heißt, es kann was passieren – technisch, sängerisch, was auch immer. Auch mit der besten Vorbereitung und mit den besten Voraussetzungen: Wir sind alle nur Menschen. Wir versuchen unser Bestes zu geben. Aber es gibt keine Garantie.

Hat man vor dem Bayreuther Publikum als Sänger vielleicht sogar Angst?Bieber: Mit Angst darf man nicht auf die Bühne gehen. Wer Angst hat, ist verkrampft. Und das ist fürs Singen gar nicht gut. Man muss Respekt vor dem Publikum haben. Ich habe bisher noch keine schlechten Erfahrungen mit dem Bayreuther Publikum gemacht.

Read the whole interview in Mainpost.de

Clemens Bieber in Bayreuth

(notes on Deutsche Oper Berlin's Facebook Page)

1.

"Wie so oft in Bayreuth: es regnet und es ist kalt, aber wir beginnen mit den Proben, Tannhäuser schon eine Woche und Tristan und Isolde seit Montag. Viele Kollegen sind schon hier, auch die Deutsche Oper Berlin ist gut vertreten auf und hinter der Bühne und es freut einen immer wieder, alle Kollegen zur Festspielzeit wiederzusehen. Der Chor beginnt auch diese Tage und allmählich füllt sich der Hügel!"

2.

Stefan Herheim ist da und wir proben seit Mittwoch PARSIFAL! Diese Produktion macht soviel Freude, dass sogar die Proben wie im Fluge vergehen ( was nicht immer ist!!). Es geht entspannt und doch sehr konzentriert zur Sache und wir freuen uns auf unseren neuen Parsifal Simon O'Neill, der in der neuen Spielzeit auch wieder an der Deutschen Oper Berlin gastieren wird (im Trovatore). Allmählich sind alle eingetroffen, nur das Orchester fehlt noch, was die hiesige Gastronomie natürlich mit schweren Umsatzverlusten ausbaden muss!! Aber bald sind ja unsere Orchesterfreunde da.

3.

Bayreuth im Hitzestau, es ist eine "Freude" bei über 30° in einer Industriehalle Parsifal zu probieren, man kann gar nicht soviel trinken wie man schwitzt. Aber nach viel Regen heute Nacht sind die Temperaturen wieder erträglich und jetzt sind auch alle da, das Orchester hat heute mit den Proben begonnen. Und nun geht es zügig voran, Orchesterproben und Bühnenproben lösen sich ab, mit Tristan beginnt es, für Parsifal stehen heute wichtige Bühnenproben an, vorallem die vorzügliche Bühnentechnik ist hier gefordert. Und dies muss ich auch mal erwähnen: was die Techniker gerade im Parsifal leisten ist unglaublich und bewundernswert, übrigens auch etliche Kollegen von der Deutschen Oper Berlin!!

Colin Bayliss • Clemens Bieber • Bea and Alec Bobotek • Stephen Charitan • Gary Campbell • Jerry Floyd • Sam Goodyear • Janette Griffiths • Diana Herbst • Hildegaard Arnold Kiel • Randall G. Malmstrom • Anne Midgette • Walter Meyer • Wouter de Moor • John F. Runciman • Per-Erik Skramstad • Brian Slater • Julia Thornton • Natalie Tsang • Mark Twain •

August Wagner – Bayreuth

We two, mother and son, made the pilgrimage to Bayreuth this year after attending Seattle's second 2009 Ring cycle. Bayreuth was this year just as Bea remembered it from 2002 – a beautiful little center of Wagner worship with the devout arranging their schedules around the four o’clock opera start time.

That unvarying fact dictated busy mornings of elaborate breakfasts, museum schedules, conversational exchanges about the performance of the night before or the current state of the festival management, as well as other temptations: the shops and the lectures, the latter sponsored by the New York Wagner Society, this year by Hans Rudolf Vaget, Professor Emeritus from Smith College (and editor of a journal of Wagner studies, among other things).

The Parsifal of August 27 was performed in a very warm Festspielhaus but turned out to be so riveting that somehow the oppressive heat hardly seemed to matter: remarkably, there were no audience casualties. The next evening brought considerably cooler temperatures but a less-than-memorable Tristan production. The net result, perhaps predictable: by the last act, the audience suffered casualties requiring semi-conscious members to be carried from their seats. How fortifying a fine Parsifal can be.

Parsifal

Our Parsifal was indeed very fine, but involved much extrapolation of the modern history of Germany and accompanying references to swastikas and the like. It also featured the first childbirth scene (of Kundry) that we remember seeing in a Parsifal. There were strong visual icons – bed with trap door in stage center, fireplace/hearth, and a clock that seemed to measure social progress rather than time. Its elaborate sets, costumes, technology (electric and pyrotechnic spears, visual projection), visual icons, and concurrent telling of a second story worked well, providing overall a most complex and rich opera experience of music, theatre, and story. There were zero boos and plenty of heartfelt bravos from the audience – despite earlier unease when the swastikas and stormtroopers made their appearance.

This production, introduced in 2008, is the work of Stefan Herheim who combined, as implied above, “various aspects of current European stage styles, psychological realism with symbolism and metaphor, between the text inferences, and influences of surrealism” (our translation of phrases from a German-language booklet on the production by Suzanne Vill). Included in the metaphoric staging were scenes not only of the progression of German history on film, but also visual references to Haus Wahnfried as the characters of Parsifal and Herzeleide were shown in childhood and in varying stages of growing up, particularly in the case of Parsifal. The first scene included a rocking horse.

One suspects the staging has strayed too far when one must rely on the director’s off-stage narratives to explain the progress of events. But all in all this was an involving, fascinatingly conceived production.

Tristan

By any measure, Tristan was a very flat performance. The production opened on a flat stage with two padded stools at stage front and two wooden and glass-enclosed booths next to each other at the back. Isolde and Brangäne sat on the stools huddled tightly next to each other, while Tristan and his envoy emerged and returned to their respective booths at their entrances. The potion drinking episode did provide a bit of drama, at least.

The final act had Tristan in a bed horizontally placed on the stage, with Isolde singing and expiring in the bed after having embraced the dead Tristan who by that time lay on a stretcher in front of the bed. There was some play of lights in the ceiling and on the walls of the theater, coarsely reflecting the day and the night.

Since Tristan is really all about expression through musical means, we can report that Peter Schneider conducted the festival orchestra with relaxed aplomb even if somewhat perfunctorily at times, and that Tristan (Robert Dean Smith), King Marke (Robert Holl), Kurvenal (Jukka Rasilainen), and Brangäne (Michelle Breedt) were faithfully and artistically portrayed and with satisfyingly fresh vocal resources. Robert Dean Smith performed with considerable security, much as he had in the recent Met broadcast performance. On the other hand, the Isolde of Iréne Theorin was a major disappointment given the excitement built around her unexpected Met debut as Brünnhilde. The Swedish soprano sang shrilly at the top, and with surprisingly poor diction. So, all in all, thumbs down for this production.

Wahnfried

The day after the festival’s end, there was a quick exodus from the hotel, and many restaurants curtailed their hours of service, as did our hotel, the Arvena Kongress. But no problem, we had scheduled a visit to Wahnfried, which with its expansive proportions including an open air atrium and lavish possessions, artworks and furnishings belie the indebtedness of its original owner.

A high point of our visit was an unscheduled recital, for just three of us, by Hungarian pianist Jenö Jandó who, during our visit to the Liszt house and museum across the street from Wahnfried, had persuaded a delighted curator to allow him to play one of Liszt’s pianos (formerly used by Wagner while he was working on Parsifal).

Colin Bayliss • Clemens Bieber • Bea and Alec Bobotek • Stephen Charitan • Gary Campbell • Jerry Floyd • Sam Goodyear • Janette Griffiths • Diana Herbst • Hildegaard Arnold Kiel • Randall G. Malmstrom • Anne Midgette • Walter Meyer • Wouter de Moor • John F. Runciman • Per-Erik Skramstad • Brian Slater • Julia Thornton • Natalie Tsang • Mark Twain •

Bayreuth Festival 2011

REGIE RAGE: DIE MEISTERSINGER (Aug. 24, 2011) TANNHÄUSER (Aug. 25, 2011)

I had a wise history professor in college who would often say "in life you do what you can." His words came back to me when I was deciding to attend the 2011 Bayreuth Festival - a year that promised relentless regie, no Ring, and with a few exceptions, "B list" casting. As things worked out 2011 became possible and I thought I would follow my professor's advice. If all else came up a cropper, I could still rely on that magnificent acoustic, the superb orchestral playing, a grand chorus, and the magic of being in Wagner's own theatre. Things got off to a rocky start with Katarina's "upside down" Meistersinger, my second go at this shock schlock. Who would ever think to be discussing masturbation, defecation, and full frontal nudity in conjunction with a performance of Die Meistersinger, but all could be had for the price of a ticket. Worse than any of that nonsense however was the fact that not one character was directed to show any human emotion towards another - this in one of the most warmly human works in the repertory. Strangely enough, what kept this directorial Hesperus from being a total wreck was the singing. Though too young in both voice and appearance, James Rutherford sang Sachs with a rich, rolling baritone. He retained those qualities through to the end of a long evening. Norbert Ernst brought a strong, almost stentorian sound to David but still managed a fluid, cantiblie line. His was one of the finest musical interpretations of this role I've experienced, and fortunately the production couldn't find a way of working him into the concept so the character was more or less left alone. Michaela Kaune unfortunately played an Eva who was not beloved of any of the other characters, or more accurately, "concepts" passing for characters, but she sang "O Sachs, mein Freund" with passion and soared with purity though the quintet. The Walter was Stefan Vinke substituting for Burkhard Fritz. Vinke has a clear, ringing, not unpleasant sound that functions at two dynamic levels - loud and louder. Adrian Eröd brought a lean sounding comprimario’s voice to Beckmesser, but carried the bulk of the “concept” on his shoulders. Though it made no sense given the archaic sound Wagner created for Beckmesser’s music the conceit of the production was to turn this arch conservative into a non conforming revolutionary. Eröd did yeoman work in trying to consistently sell this character twist within the jumble of irrelevant stage business swirling around him. Sebastian Weigle's routine conducting couldn't compete with the shenanigans on stage, but the band played beautifully for him, as it did the remainder of the week. Next day's Tannhäuser trumped Meistersinger for offering a production which had virtually nothing in common with the details of the libretto at hand or the sound picture created by a German composer of the mid 19th century. The Venusburg was a cage that contained, in addition to a pregnant goddess, a variety of hairy, humping, humanoids, several outsized tadpoles, and one other creature of indeterminate species that looked like a cross between an ambulatory flounder and a turtle standing on two legs. I suppose this whole set up was some sort of metaphor for the baser animal instincts - nothing sensual or voluptuous about this Venusburg, including the Venus herself. Stephanie Friede gave what was arguably the worst vocal performance of the 5 opera set. When this mess sunk into the floor boards we were assaulted with Wartburg® - a waste recycling facility where at one point the “employees” were dumping excrement (tilted towards the audience so it was impossible to miss the point) into some sort of pressure vessel. This ghastly factory, filled with a robotic chorus was Tannhäuser’s alternative to the equally unappealing Venusburg which probably explains Elisabeth’s “assisted suicide” in the 3rd act. After Camilla Nylund delivered a beautifully poised prayer, momentarily eclipsing the dreck around her, she climbed the stairs surrounding a large circular tank followed by Wolfram who helped her into its steaming belly. Again making sure to club the audience over the head with shock value, Elisabeth tries to push her way out of the tank / gas chamber, but Wolfram shoves her back in and closes the door. Michael Nagy, a handsome young artist with a smooth, caressing voice and a lieder singers feel for nuanced phrasing goes on to address his hymn not to the Evening Star but instead to the pregnant Venus. Tannhäuser himself gets rather lost in all of these goings on. Swedish tenor Lars Cleveman had the requisite weight of voice and strength of technique to sing, not bark the role right through the Rome Narrative but what he lacked was an ability to connect with the character and his dilemma. He could hardly be held accountable since subtext and sub sub text were what concerned director Sebastian Baumgarten, not the inconsequential trials and tribulations of the title character. Conductor Thomas Hengelbrock has had some experience as an Early Music specialist. Possibly for that reason I was more aware of a certain “rum ti tum” quality in this early Wagner that I think more experienced conductors of this repertory know how to balance or smooth over with greater effectiveness. With the boos still echoing in my ears from these two performances, I was looking forward with some trepidation to what would come next – would Lohengrin, Parsifal, Tristan and Isolde rise above this relentless regie? Stay tuned for Part 2.

REGIE REDUCED: LOHENGRIN (Aug. 26, 2011)

Day 3 promised Lohengrin and his rats. After more than 30 years of opera going I’ve found one maxim to be generally true – A genuine star performer can usually trump his or her surroundings – marginalizing regie, compensating for inadequate colleagues, and though a particular challenge in Wagner, offsetting a routine conductor or orchestra.

Over the past few years Bayreuth has been very lucky in capturing the commitment of one of these rare creatures – Klaus Florian Vogt. First off is a singularity of voice. Once heard it is impossible to mistake the clarion purity and almost choir boy cleanness of his sound for anyone else’s. He began his career as a horn player which might also account for the beauty and sensitivity of his phrasing. Add to this a handsome stage presence quite in keeping with the heroes of his current repertory. In short, the man “looks like” the voice. I’ve seen Lohengrin many times – this for me was the standard bearing performance of the title role. The audience at the August 25th performance awarded the leading man with a standing, stomping ovation.

Fortunately Bayreuth provided an appropriate setting for Mr. Vogt in terms of cast and conductor. Annette Dasch is a vivid actress with what could be described as “Bette Davis eyes.” I imagine she effectively registered to the back of the house without implying there was anything of the caricature about her Elsa. Vocally she lacked the ethereal float to make “Euch Luften” and the tender sections of the bridal scene the time stopping moments they can be but her strong, clear sound and urgent delivery brought the determined obsessiveness of the character front and center. Petra Lang was diminutive in stature but supersized in voice as Ortrud. She was a delicious fairy tale witch from top to bottom though I suppose a lack of subtlety might be argued. One of the memorable visuals in this production was to see Elsa and Ortrud in their big feathered ball gowns maneuvering around each other like white swan vs black. Tómas Tómasson, Georg Zeppenfeld, and particularly Samuel Youn as Telramund, Heinrich, and the Herald respectively all offered noble support. Andris Nelsons conducting was the most dramatically compelling of the 5 performance set.

I leave the regie til last because it had the least to do with the success of this performance. On the credit side were many striking visuals in terms of simplicity of image, and use of brilliant color. The staged prelude boded well. In it Lohengrin is seen pushing back a stark white wall as if this archetypal outsider somehow wanted to get in. Did he want in to rescue and reform or did he want in to conform and be accepted? Unfortunately, as with the Tannhäuser travesty the plight of the main character is saddled with an artificially inflated subtext that leads me to the rats. Unlike the choruses in for example, Boris Godunov, Khovanschina, Aida, and Turandot where they play a real role in the unfolding of the drama, the chorus in Lohengrin is largely there to comment on the action, not drive it. Here by dressing them as rats, sometimes white, sometimes black, and pink for the babies (twee comes to mind…), they immediately signal in large semaphoric gestures that they are bearing “the director’s message.” The rats are obviously in some sort of laboratory setting and first they seem to respond to the Hearld who is acting as a sort of proxy for, or is it more of a Martin Bormann / Dr. Morrell type to, a demented and confused Heinrich. Later on they switch their allegiance to Lohengrin – wearing uniforms with a capital “L” on their belts long before he reveals his name and heritage. Is it all about fascism (again…) and who is controlling the people / rats – Lohengrin, Heinrich, or - why not - even the Herald ? Perhaps they should graft on the Steersman or Mary from Dutchman just to mix it up a bit more? Thanks to the transcendence of Wagner’s music, the glorious vocalism of Klaus Florian Vogt and an accomplished cast and conductor I think the rats and their message became largely irrelevant.

REGIE REDEEMED: PARSIFAL (Aug. 27, 2011)

If you've followed me up to this point you might think I was violently opposed to "Regie" of any kind. That is not the case because Bayreuth's "Parsifal" courtesy of Stefan Herheim represents "Regie in excelsis." Maybe libretto and "concept" are not completely in sync in terms of minute details, but as to the bigger themes there is a tangible and direct connection that truly ignites the relationship between the music, the libretto, and the director's point of view. From a production standpoint, "Parsifal" was the pinnacle the 5 opera run - and adding to the triumph, the music making was nearly on as high a level. Herheim's concept is to equate the birth of Germany as a unified nation (1871) with Wagner's composition of Parsifal (music begun in 1877 - libretto 1857). The firm underpinning that brings these two milestones into confluence is the fact that both the country and the character are on a journey. Despite the degradation and shame each protagonist accumulates on that journey, the outcome is ultimately survival, reconciliation, and even progress through lessons learned. I saw this production in '09 and was so completely taken by its cumulative impact that I was blind to what I now see as an excess of ideas in Act 1. As if in an expressionistic dream, the prelude starts with a dying Herzeleide trying in vain to reach out to Boy Parsifal in Villa Wahnfried. As the act proceeds, this is mixed up with images of the Wittelsbach monarchy (both Amfortas and Boy Parsifal wrapped in the iconic blue ermine trimmed coronation robes of the dynasty) , intimations of an Oedipal relationship between the hero and his mother, and finally a mute Klingsor dramatically appearing out of a picture above a Wahnfried fireplace as a harbinger of a sensual corruption that would reach its apogee in a Weimar inspired Act 2. By the end of the first act depicting soldiers of WWI vintage gathered outside of Wahnfried, through the unfurling of Nazi swastikas, and the destruction of Wahnfried at the end of Act 2 the production gains a force, focus and momentum that never wavers until the breathtaking finale in the modern Bundestag that ends Act 3. Quite frankly experiencing the brilliance of Herhiem's "thought through" vision for Parsifal only emphasized the amateur, sensationalistic, and all too facile efforts of K. Wagner, S. Baumgarten, and H. Neuenfels for Meistersinger, Tannhäuser, and Lohengrin respectively. Of the 5 productions of this year's set, only this Parsifal would be worthy of Wagner's dictum: "Kinder, schafft Neues!" As to the musical performance, Simon O'Neill as Parsifal had something of the clear, focused sound that Klaus Florian Vogt brought to Lohengrin but unlike Mr. Vogt, the "nap" was gone and the voice lacked the spin of youth. Susan Maclean, though listed as a mezzo, brought a bright voiced soprano like timbre to Kundry. She was an intense, committed actress and made the most both vocally and dramatically of her big moments in Act 2. I would welcome the opportunity to hear her in this role again. The vocal standout of the 2011 Parsifal was Kwangchul Youn as Gurnemanz, just as he was in2009. The smoothness of his voice and the fluidity of his phrasing makes you appreciate why Wagner valued an Italianate / cantabile sensibility for singers of his operas. Would he have the same effect in one of the Big Barns typical in the U.S? In the Bayreuth acoustic as well as the greater world outside The MET such questions hardly matter. Thomas Jesatko as Klingsor channelling Marlene Dietrich can be as proud of his "gams" in a garter belt as he can be of his vocalism. Detlef Roth was a dry voiced, but dramatically effective Amfortas. It is so easy to become spoiled by luxury casting in this role remembering George London or more recently Thomas Hampson. Finally tying all together for the most successful totality of the 2011 run was the leadership of Daniele Gatti in the pit.

REGIE RECONCILED: TRISTAN UND ISOLDE (Aug. 28, 2011)

If my perception of the Bayreuth / Stefan Herheim “Parsifal” was “Regie Redeemed” than my second viewing of the Christoph Marthaler “Tristan und Isolde” might be called “Regie Reconciled.”

When I first saw this Tristan in 2009 it reminded me of something that might have been designed in the former DDR and outfitted from IKEA seconds. With its peeling wallpaper and dirty furnishings it still remains one of the most physically ugly settings I’ve seen vomited up on any stage. Three things however made this year’s experience significantly different and much more satisfying than ’09’s:

- Visually I knew what I was in for, so there was no shock or surprise element when the curtain went up. I approached the work as if I were going to a concert. Assuming a great musical performance Tristan und Isolde is one opera where stage setting can be immaterial because so much of the "action" is internal.

- My friend and I were sitting in row 7. From there it was much easier to focus on the expressions and body language of the individual singers without having to take in the whole bloody mess that I was forced to deal with when sitting further back. Because of their proximity, the singers themselves became the mise-en-scène.

- Most important of all, the eponymous characters were both on fire for what was the last performance of this season.

This “Tristan und Isolde” brought home to me once again the obvious fact that singers carry their instruments in their bodies. They are therefore subject to a variety of natural influences that impact a result that is not so much definitive, but rather that is a moment in time. We live for those nights when all the essential elements for something transcendent are in alignment - this was one of them. In ’09 Irene Theorin’s Isolde was loud, unsubtle, and seemed to have no warmth in the all important (for this role) middle voice. Her 2011 performance was a revelation, powerful, nuanced, and deeply felt. I was struck again and again throughout the evening by the sheer beauty and richness of her sound from hushed pianos to blazing, raging highs. I’ve heard many a fine soprano falter at Isolde’s final “Lust…” Theorin absolutely nailed it. This is an essential phrase that can leave the theatre with you and color memories of all that went before. In ’09 Robert Dean Smith rather saved himself through Acts 1 and 2 and then went on to deliver the finest Act 3 in my experience. Here his performance was more of a piece and proved in the right surroundings the traditional heldentenor heft is not a prerequisite of success in this role. His lean, youthful sound and almost “everyman” demeanor somehow made the character more heroic and certainly more poignant than many of the gruff, barking baritenors I’ve heard in the part. Mr. Smith also SANG beautifully right to the very end.

While its an added plus to have Brangäne, Kurwenal, and especially Marke cast from the “A” list the work does not pivot on their contributions.

Bayreuth had a solid cast of what might be termed “house singers” in these roles - Michelle Breedt, Jukka Rasilainen and Robert Holl respectively.

Peter Schneider has a long history of conducting at Bayreuth going back to 1981. Because he is not one of the glamorous names often associated with this repertory it would be easy to dismiss him as a routinier. Never once did he overwhelm his cast yet there was no sense of stinting or damping down. His long experience with the unique acoustic made for some gorgeously blended sound pictures. A lingering memory for me will be the Act 2 Liebesnacht when Schneider, the orchestra, Theorin and Smith all caught the pulse of the music, suspended time and magically became one entity.

In the course of 5 nights I went from Regie Rage, to Regie Reduced followed by Regie Redemption, and finally Regie Reconciliation. All of that however is incidental to why one would take on the time and expense of a trip to Bayreuth. The reason remains what it always has been and probably always will be – the ability to hear some of the most intellectually complex, spiritually enhancing, and emotionally satisfying music ever composed in an acoustic uniquely designed for just that purpose.

Colin Bayliss • Clemens Bieber • Bea and Alec Bobotek • Stephen Charitan • Gary Campbell • Jerry Floyd • Sam Goodyear • Janette Griffiths • Diana Herbst • Hildegaard Arnold Kiel • Randall G. Malmstrom • Anne Midgette • Walter Meyer • Wouter de Moor • John F. Runciman • Per-Erik Skramstad • Brian Slater • Julia Thornton • Natalie Tsang • Mark Twain •

A "Meistersinger" experience in Bayreuth

As a member of Friedelind Wagner’s Master Class at Bayreuth for two years and another season as a visitor, I have had many unique experiences at Bayreuth. Of course, most must be kept confidential until the parties have died, but there are still memories that can be shared.

One of the most engaging was during a Meistersinger performance conducted by Hans Knappertsbush.

I was most fortunate to be able to sit in an unoccupied seat for both a Meistersinger and a Parsifal performance in the orchestra pit, and was able to watch the maestro close up, and in a wonderful environment. What an experience!

The Meistersinger performance remains most vivid to me (even though it's not a favorite opera of mine). Of course I was very young at the time, and had no idea of the gravity of any experiences that I was privy too, either in performance, rehearsal or personal (Wagner family activities especially!. Believe me there were many).

However – Meistersinger: During the final moments of Act II, it seems that the Night Watchman mixed up his words, and from what I gather, repeated his lines from his first entrance, rather than the hour later, which was required. All this was unclear from the sound that reached the pit.

Herr Kna. shouted something very loud, that I did not understand, at the singer on stage, with appropriate threatening gestures. I of course, could not hear the singer, being at the lowest level of the orchestra pit. The orchestra members seemed amused by this, but I doubt if they heard the mistake either. BUT!

The outraged Maestro threw down his baton and leapt off the podium. My impression, from what I knew of the Festspielhaus configuration, was that he disappeared totally from the singer's view on the stage. He proceeded to sit on the stage-right side of the conductor’s raised platform and pulled out a pack of cigarettes, lit up, and puffed until the end of the act! The orchestra continued, stifling giggles: the fire dept probably had fits, since the whole theatre is a tinderbox, (live flames, at least at that time totally verboten) and yet the audience had no idea what was going on. The act ended without a conductor! I really felt sorry for the singer who made the minor mistake. Certainly a moment I treasure! AND, a moment that the singer probably still has nightmares about!

But there is more...

Colin Bayliss • Clemens Bieber • Bea and Alec Bobotek • Stephen Charitan • Gary Campbell • Jerry Floyd • Sam Goodyear • Janette Griffiths • Diana Herbst • Hildegaard Arnold Kiel • Randall G. Malmstrom • Anne Midgette • Walter Meyer • Wouter de Moor • John F. Runciman • Per-Erik Skramstad • Brian Slater • Julia Thornton • Natalie Tsang • Mark Twain •

Gwyneth Jones and Chéreau

In 1979, while I was interviewing Dame Gwyneth Jones in Bayreuth, the soprano put her hands around my top of my head to try to explain why I found her Brünnhilde so sensual. As her hands pressed against my skull, an electric charge flowed through my body.

A couple of days later, thinking I was at the Haus Wahnfried museum, I knocked on Winifred Wagner's front door. A housekeeper answered and asked if I wished to see Frau Wagner. Because my trip was funded by the West German government and there had been a furor over Hans-Jürgen Syberberg's film, Winifried Wagner und die Geschichte des Hauses Wahnfried, I declined the offer. A mistake I regretted almost immediately and even more keenly after Frau Wagner died the following year.

In that pre-internet era, critics could only transmit reviews to newspapers via telex and all telex time was reserved by other writers. As soon as I completed attending seven Bayreuth performances, I took a train to Frankfurt, to file my review at the city's Associated Press (AP) office. The route from my hotel to the AP went through Frankfurt's red light district. Alhough I had watched Wagner's Blumenmaedchen cavort onstage in the Festspielhaus less than a day earlier, I was startled by the graphic, lurid erotic displays in many of the city's shop windows. I overcame my shock and my review was soon filed in Frankfurt and published in the now-defunct Washington Star.

I wrote of my admiration for Harry Kupfer's stunning Der fliegende Holländer but panned the Patrice Chereau Ring, using a snide term, "Chereaudaemmerung", to describe the production. A year later this Ring was taped and when it was telecast in the U.S., I realized how wrong I had been. I also completely understood why Dame Gwyneth expressed her enthusiasm about Chereau's direction in such a sensual, tactile way.

After seeing the Chereau-directed production of Janacek's From the House of the Dead at the Metropolitan Opera in December 2009, I am ever more convinced that Chereau is one of our very greatest directors. Since the centenary Ring cycle at Bayreuth, Tristan und Isolde is the only Wagner work that Chereau has directed. Here's hoping he directs Parsifal sometime soon.

Quite coincidentally, I saw Catherine Zeta-Jones in Sondheim's A Little Night Music in New York, just two days before the Janacek opera. Like Dame Gwyneth, Zeta-Jones is Welsh and the actress's lovely, lilting voice, her physical beauty, and sensual stage presence made me think of my encounter with Dame Gwyneth at Bayreuth 30 years ago.

Colin Bayliss • Clemens Bieber • Bea and Alec Bobotek • Stephen Charitan • Gary Campbell • Jerry Floyd • Sam Goodyear • Janette Griffiths • Diana Herbst • Hildegaard Arnold Kiel • Randall G. Malmstrom • Anne Midgette • Walter Meyer • Wouter de Moor • John F. Runciman • Per-Erik Skramstad • Brian Slater • Julia Thornton • Natalie Tsang • Mark Twain •

First visit to the Bayreuth Festival

My parents like to remind me that when I was a small child, each year in the run up to Christmas I would become so excited that I would begin to feel ill. Sleeping the night before was impossible for me, with the idea that I might receive the latest offerings from both Sega and Nintendo simply too distracting a prospect. Could I really have a lifetime’s supply of Golden Apples and the Ring?! I’m almost certain that my six-year-old self would have renounced all love for a copy of Sonic the Hedgehog 2, but thankfully I was never given the option.

I mention this because, more than 20 years later, it is as close as I can get to describing how I felt the night before my first visit to the Bayreuth Festival. At some point in the previous year, I had talked with my girlfriend Jeanette about how wonderful it would be for us to attend a performance on the Green Hill one day. It is safe to say I never imagined that day would come this year, but after chancing on the news that some online tickets had been returned (via internet blogger Intermezzo, to whom I am indebted for the information), we began making our summer-holiday plans around a performance of Tannhäuser.

Staying in Nuremberg, we rose early on the morning of the performance so as to give us plenty of time to get there in the event of any last-minute hitches with the train service. If the disrupted sleep the night before hadn’t been enough of a clue that the big day had finally, surreally, arrived, putting on a hastily cobbled together dinner suit at 8am certainly was. And then it was swiftly on to the train, where initial butterflies that we might be headed somewhere other than Bayreuth were allayed by the arrival of a middle-aged man with long hair and one eye in the seat opposite - if Wotan were going, I knew we must be in the right place.

Upon arrival we took tea and coffee on the terrace of a rather lovely restaurant just where Maximilianstrasse and Richard-Wagner-Strasse meet, and had a short look around town before setting off for the Festspielhaus. Walking up to the building itself, I was put in mind of the opening of those DVD recordings of old festival productions, when one follows the camera up Siegfried-Wagner-Allee – it was magical to do it on foot. We were among the first to arrive for the day’s performance, and so had plenty of time to take some pictures, have a look around the gardens and at the monuments and memorials there, and then have a drink before the performance. And after having taken our seats, my mind again turned to the history of the festival as I saw the stage for the first time. I could almost see Windgassen and Nilsson standing there, Hofmann and Altmeyer, Jerusalem and Meier.

But what of this production though? I had read a fair bit about Sebastian Baumgarten’s controversial staging beforehand, so I knew that the director had been booed to the rafters in previous years, and that virtually nobody had a good word to say about it. Nevertheless, it is always best to make up one’s own mind about things and give everything a chance. Now having done so, my conclusion is that while the concept as a whole is flawed, there were nonetheless more than a few interesting ideas contained within it. If I may, I’ll start by outlining some of the things that did not work for me, before continuing with the happier task of talking about the things that did.

In my view, the downfall of this production really begins with, and is inextricably linked to, the genesis of the set designed by Dutch artist Joep van Lieshout - an independent art installation termed ‘the Technocrat’ containing a biogas plant and various machines that use waste to produce food and alcohol. This factory is the Wartburg, from the floor of which a large cylindrical cage representing the Venusberg rises.

Now, this in and of itself might not necessarily be a problem (although in this case I think it was). The more inherent problem stems from the fact that this installation was not designed specifically for the opera. Rather, it was an existing artwork, an exploration and study in circular systems, that the production team took and subsumed Tannhäuser into. As Baumgarten himself says in the programme notes, his idea was “to escape the hell of interpretative theatre…the opera has been integrated.”

But as much as much as he might say he wishes not to interpret the work, he does. The very nature of working in Bayreuth - with a fixed score, a specific mandate, and a ‘traditional’ performance space - means that he cannot avoid it. So having already decided the production will be ‘about’ the ideas contained in the Technocrat, he is then tasked with justifying this by somehow finding them within the opera.

What one gets then is rather like the result of someone taking jigsaw pieces that don’t fit and desperately bashing them with a hammer until they sort of stick together - perhaps some of the pieces will look alright, but the overall picture is going to be a complete muddle.

I suppose I can see how the autarkic yet interdependent functioning of the biogas plant, with everything needing everything else to properly function, could be a metaphor for our hero needing both Wartburg and Venusberg. But even accepting this point, I just don’t think the setting serves enough other, less generalised dramatic purposes to justify itself. People operate the machines at various times, and drink the alcohol, but it is all rather confusing and difficult to work out what it is supposed to relate to.

Another difficulty with the Technocrat is its complete physical dominance of the performance area, but comparative lack of use theatrically. The three-storey structure takes up a great deal of the stage in a rather intrusive way, almost creating a second proscenium arch from within. Sightlines were therefore compromised - I could not see much at all of what was projected on to the back of the stage from my seat in the right stalls. This might be justifiable if the structure were utilised and integrated into the drama, but it isn’t really. In fact, pretty much all the main action of the opera takes place at ground level. The upper floor is barely utilised at all, save for some people sleeping there. And aside from a nice image of a prayerful Elisabeth one floor up at the end of the piece, even on those occasions where major characters do appear within the installation proper there often seems to be little or no dramatic point in them being there rather than anywhere else. Given it was not designed with that in mind, why would there be?

And then there is the director’s attempt to explain the set’s existence by creating a back story. Apparently, the whole thing is actually a play within a play, and the workers in the factory like to perform Tannhäuser to break up the monotony of their lives. I really think this makes absolutely no sense at all – why would they choose this opera, and if they do, does that mean that all these animal creatures in cages are just people acting? In any case, I don’t think this back story comes across clearly in what is presented on stage; at least it didn’t to me.

I believe the most important question one must ask about any set design is ‘how does this help to bring out meaning and ideas in the work?’ For me then, the answer in this case was that it simply did not, at least not enough. It was less “obsessive installation”, more oppressive backdrop. To a certain extent one can simply ignore the Technocrat and concentrate on the primary characters, but of course that is far from an ideal state of affairs.

As much of a downside as this was, the low point of the production though was definitely the opening scene in the Venusberg. I get the message - indeed it would be hard to miss it - with the giant sperm dancing away or playing dead depending on what Venus and Tannhäuser were singing about, but it’s pretty obvious stuff and presented in truly ridiculous fashion. Maybe the crudeness of its presentation is supposed to represent the base instincts of the Venusberg? Even if this was the idea it was not a good one, as it was hard not to simply laugh, and it removed all tension and theatrical power from Tannhäuser’s decision to leave.

To a lesser extent, I was also unsure about the introduction of Venus into the song contest. I think this could have worked, if perhaps Venus had been there as a vision only Tannhäuser could see. But if the other minnesingers recognise Venus, greet her, and accept her presence at the back, why are they so angry when Tannhäuser sings his song to her? It also occurred to me that having Tannhäuser sing to Venus because he actually sees her there makes his conflict less internal, which I wasn’t sure was a good thing.

And unfortunately, there was an additional problem of the director seeming rather indifferent to the music. To be fair, some effort was made to have characters respond to the musical line during purely orchestral playing, most notably in the Prelude to Act III which provided interesting viewing. But once people started singing this largely went out of the window, and there were passages that were curiously close to old-fashioned ‘park and bark’. Given Baumgarten’s seeming willingness to engage more with orchestral music, it seemed doubly a shame not to have the Venusberg music from the Paris version.

But as I said, and I would like to emphasise this, I really did not think it was all bad. Some of the themes brought out by Baumgarten when he allows himself to simply interpret the work are I think, genuinely valid and thought provoking. For example, I did like many of the production’s attempts to reduce polarity between the Wartburg and the Venusberg, and tied in with this, I thought the idea of having Venus give birth to Tannhäuser’s child at the end was particularly interesting. As I saw it, this was not purely Venus’ child we were seeing but rather Elisabeth’s child, conceived, borne and delivered by Venus as surrogate. What we have then is a Virgin Birth, Tannhäuser’s salvation lying with Maria’s definitive act. The redemption of Tannhäuser comes with the birth of the Christ child, but only when the representatives of sensual and spiritual love work symbiotically.

I also thought the production did a good job of avoiding Wolfram simply playing Horatio to Tannhäuser’s Hamlet. The character certainly has conflicted feelings of his own and I think it is important to explore these for their own sake, as well as in contrast to Tannhäuser’s. Having him sing his Lied an den Abendstern directly to Venus, with the evening star of course being another name for the second planet out, was just one example of the production asking the audience to question Wolfram’s thoughts further. When he is thinking of Elisabeth, is his mind not also on Venus?

And whilst I have reservations, not least because it has surely become a theatrical cliché, there is at least some mileage in the strictness and orderliness of both the Wartburg and religious piety being represented by a cult-like group in an Orwellian dystopia. Aside from anything else, the sight of people being shipped off in a crate to be ‘cured’ was a reasonably powerful image depicting religious intolerance.

Moreover, musically things were largely very good. Torsten Kerl gave an admirable performance as Tannhäuser. The role’s punishingly high tessitura was negotiated without any noticeable tiring, and his tenor had enough of the helden about it while also retaining a pleasing tone. Dynamics could perhaps have been a little more varied, but then again much of the role demands volume. His acting was solid rather than spectacular, but a jack-the-lad persona in the first two acts was well conveyed.

Camilla Nylund’s Elisabeth was thoughtfully portrayed, and the strength of her theatrical commitment stood out. Perhaps this was no coincidence given that she is the only remaining principal from the original 2011 run and, as evidenced by comments from Baumgarten in the programme notes, she genuinely believes in the concept of the production. Vocally she also performed well, particularly in the middle register, lacking only a real fifth gear in terms of volume, and perhaps a touch more fullness of tone above the stave.

If I were less enthusiastic about Michelle Breedt’s Venus than some other performances, this was no doubt partly down to the fact that some of her key scenes were the ones in which I thought the director missed the target by the largest amount. Nevertheless, her vibrato was on occasion slightly too wide for my liking.

But a mention must go to Bayreuth stalwart Kwangchul Youn, who proved a fine Landgraf Hermann. He was rich in voice and authoritative on stage, and with the smaller minnesinger roles also well taken, the sextet to close the first act included some very fine singing.

The standout performance of the evening though came from Markus Eiche as Wolfram von Eschenbach, whose musicianship was of the absolute highest quality. A beautiful tone was allied to careful phrasing, dynamics and attention to words, which coupled with equally strong acting skills meant that his Ansprache and Lied an den Abendstern were genuinely moving, and two of the highlights of the evening.

Moving away from the principals, the chorus demonstrated effortless power and the final reprisal of the Pilgrim’s Chorus was literally spine tingling. There were some instances of a machine-gun approach to final consonants which could have been tidier, but this did not detract very much from the overall effect.

The sound of the orchestra from the famous covered pit was one of the things I was most looking forward to experiencing live for the first time and it did not disappoint. The strings shimmered, the trombones were beautifully mellow, and oboe lines seemed to be coming from the ceiling. I’m not sure how much of the orchestral texture was down to the acoustic and how much was down to Axel Kober’s direction in the pit, but there were certainly some beautiful sounds produced. Kober’s tempi were I think largely uncontroversial, and at least to my layman’s ears he seemed to give a good account of the score.

All in all then, despite its flaws I found the production interesting and enjoyable. The rest of the audience seemed to as well, with all the principals, the chorus, its master, and the conductor receiving sustained appreciation at the curtain. One man a few rows behind me did shout something during the staged Eucharist just before the beginning of Act 3 which Jeanette reliably informed me translated as ‘get off, this has nothing to do with opera’. But he was joined by only a few fellow Neanderthals, and seemed more a source of amusement to most people around him. If only I spoke German, I would have informed him that if there is one thing in the world that definitely has nothing to do with opera, or indeed any art, it is that sort of behaviour, but alas. Sebastian Baumgarten was not in attendance so we’ll never know what the reaction would have been to him on that particular night.

And that was that. Just enough time to take one last look at the Festspielhaus, grab a McDonald’s and get the last train back to our hotel. Sublime, ridiculous and all that. It’s now two weeks since we flew back to England, and the whole trip still seems just as wonderful as it did at the time. I really can’t say enough about how special the experience of attending the festival was, and I feel very lucky to have been. Both Jeanette and I are in agreement that it was one of the most amazing days we’ve ever had, and we simply can’t wait to go back again.

Colin Bayliss • Clemens Bieber • Bea and Alec Bobotek • Stephen Charitan • Gary Campbell • Jerry Floyd • Sam Goodyear • Janette Griffiths • Diana Herbst • Hildegaard Arnold Kiel • Randall G. Malmstrom • Anne Midgette • Walter Meyer • Wouter de Moor • John F. Runciman • Per-Erik Skramstad • Brian Slater • Julia Thornton • Natalie Tsang • Mark Twain •

Janette Griffiths: First time at Bayreuth

On a hot summer's evening in Paris in 1988, two French friends phoned me from a Bed and Breakfast in Bayreuth, Germany. Marc and Pierre were preparing to go to the opera. Nothing new - Marc and Pierre spent their lives preparing to go to the opera. Or in the case of Pierre, the more emotional of the two, recovering from going to the opera. Pierre lived his "vie lyrique" as he described the abiding passion of his life, at a very intense level. Joan Sutherland's final "Lucia" left him too moved to speak for 24 hours. "Parsifal" in virtually any production, would leave him in a week-long state of swoon. And that evening, there they both were, Pierre, the emoter, and Marc, the organizer in a Bed and Breakfast just a few yards from the Festspielhaus. The following day would see the beginning of "Der Ring des Nibelungen." This Ring cycle would also mark the debut of a respected but not particularly well-known British bass, John Tomlinson, in the role of Wotan.

I did know Tomlinson's work. I had seen him sing to his coat as Colline in La Boheme at the ROH, and in the much more spectacular role of Baron Ochs in Strauss's Rosenkavalier at ENO. I knew that this was a Titan of a man onstage. Tomlinson, as Wagner's flawed and troubled god, could it seemed, move the character away from the gloomy, stately old man of some earlier productions and bring his volcanic energy to a much younger incarnation. I'd told my French friends as much. Thanks to Marc, the organizer, they had applied for Bayreuth tickets a couple of centuries in advance and were headed for a local bierstüberl in happy anticipation of an early sausage supper and a great evening of opera.

I, on the other hand, seem to lack the bit of the brain that plans. I had no ticket to Bayreuth but, as an Air France employee, I did have free air travel. Two minutes into my conversation with Pierre and I knew that I had to jump on a plane to Nuremberg and ride a train to Bayreuth where I would take my chances at getting a last minute ticket for the following day's Walküre..

Next day, there I was, walking for the first time in my life up the green hill to the Festspielhaus. I would like to say that I was moved and excited but, in truth, I was frazzled by the travel and anxious that this was a barmy undertaking that would leave me locked outside the theatre. A small part of me hung on to a hope that I would get a returned ticket. Looking at the stately opera-goers headed up the hill was heartening. Many of them were quite old, some a tad infirm. Surely somebody would keel over before Die Walküre started?

Mark and Pierre were happily anticipating their evening. So, I saw at the top of the hill, were scores of hopeful, would-be opera-goers. Ticket hunters were everywhere and all more organized and alluring than I could ever hope to be. There were women and a few men dressed as Brünnhilde. There were several Wotans and even a couple of Hundings. Some people had drawn cartoons on posters explaining their need for a ticket. Others held up simple banners. I had nothing.

The trumpeters came out onto the Bayreuth balcony to summon the audience. Marc and Pierre wished me luck and disappeared inside. So did most of those resourceful hopefuls. Soon, the bustling little square in front of the theatre was empty - except for me and the Bayreuth fire engine, oh and an English couple with their teenage son who had drawn lots: one act per family member.

I lost heart and drifted back down the hill to have a cup of tea on a patio next to the more ornate old Margrave theatre. In all my years of opera-going, I had never failed to get in at the last minute. I would always declare airily that: "Wagner (or Puccini or Verdi or Strauss) knows I love him and will look after me." They always had but now, in his spiritual home, Wagner had abandoned me. Forlorn and disappointed I wandered back up to the theatre. I even walked round it a couple of times, thinking that I might be able to hear something, anything but all I could hear was birdsong and the distant hum of traffic. The audience spilled out. Pierre and Marc were in a state of high excitement. "Tomlinson est epoustouflant!" cried Pierre. "C'est un Wotan volcanique! Titanique!" Well yes, I knew that. "C'est la plus grand soirée de ma vie lyrique!" added Pierre never a paragon of tact. And back they all went inside - all except me. I wandered around the lovely gardens on the hill, admired the flower beds and tried to take consolation, as did all my great composers, in nature. But roses and beech trees and blackbirds brought no comfort that evening. I debated returning to the B and B but I couldn't resist returning to the Festspielhaus one more time. The audience flooded out into the gardens after the second act. Pierre was in near-swoon again when, Marc, ever calm, logical and organized said, "Now that you are here, why don't we see if you can, perhaps, just look inside the theatre?" He led me towards the door and up the stairs. Nobody stopped me. I was walking up the stairs inside the Bayreuth theatre! Soon I was in the box that Marc and Pierre were sharing with two other people. The auditorium was empty during the long meal-length interval. I could gaze at the theatre and imagine all that I was missing. I had settled for doing just that when I heard Marc asking a passing usherette if "Madam could, perhaps, just stand at the back of the box for the last act?" "Why would she do that?" asked the usherette, "when the other people went home and she can sit down?"

I was in! And I was in for Wotan's great farewell, what I consider, the most moving and beautiful passage in the whole Ring Cycle if not in the whole of western music. The lights dimmed, I took my seat. I did not, of course, see Barenboim making his way to the podium. This was, after all, Bayreuth where he was probably in blue jeans and t-shirt under the roof that Wagner himself had decreed should be installed over the orchestra pit. So in the absolute darkness that is Bayreuth, I waited for the arrival of the Valkyries, and, later for Wotan/Tomlinson himself. I would like to say that I sat thrilled and moved beyond description. I would like to say that, as for Pierre, it was the greatest evening of "ma vie lyrique." However, the shock of my sudden arrival overwhelmed the performance itself. Throughout the Valkyries ride and the first entrance of Wotan, I was too stunned to take in much of the action onstage. And when I did...when I finally did …

Well, the Kupfer production was thrilling in its energy and drive but visually his use of geometric, laser-lit shapes was disappointing and unexciting. As for Tomlinson, well he played Wotan as he would continue to play him for most of his career - as a raging, foaming at the mouth, mad-dog of a god. Alas, and how heartfelt is that 'alas', I never quite agreed with that interpretation. Vocally, back then, the man was stupendous and tireless. Neither he nor any of the other singers were served by a production that, while exploding with energy, still lacked visual excitement. Dark, dark sets and dreary laser cubes of light replacing Wagner's flames. For me Sir John found his Wagnerian calling when he went on to pour that unflagging drive and energy into Hans Sachs in Graham Vick's gorgeous production at Covent Garden. There we had one of the greatest performances of the 20th century.

Janette Griffiths is an award-winning journalist and novelist who writes on travel and culture for national newspapers in the UK. Her novel "The Singing House" about a great Wagnerian bass-baritone was described by Booker Prize winner, Hilary Mantel as "unashamedly romantic, crisp and witty." It was recently launched on Kindle as an inter-active story complete with links to live performances of the Wagner and Verdi operas that drive the narrative. Janette has lived in Paris, Chicago and Florence and currently divides her time between London and Vancouver. She has a batch of blogs on subjects including Italy, France and Wagner. Links to them all can be found at www.janettegriffiths.com

Colin Bayliss • Clemens Bieber • Bea and Alec Bobotek • Stephen Charitan • Gary Campbell • Jerry Floyd • Sam Goodyear • Janette Griffiths • Diana Herbst • Hildegaard Arnold Kiel • Randall G. Malmstrom • Anne Midgette • Walter Meyer • Wouter de Moor • John F. Runciman • Per-Erik Skramstad • Brian Slater • Julia Thornton • Natalie Tsang • Mark Twain •

On the Hallowed Green Hill at Bayreuth…

Walking up the green hill through the gardens to the Festspielhaus at Bayreuth sets the mood for memorable performances of Wagner’s music dramas. What attracts so many of us to Wagner’s works is the all-encompassing physical and emotional response to the music, words and visuals on stage.

Der Ring des Nibelungen, August 2008

![]()

Götterdämmerung. Photo: Enrico Nawrath/Bayreuther Festspiele

The current production of Der Ring des Nibelungen by Tankred Dorst did not disappoint. The production complemented Wagner’s music and text beautifully.

Dorst set the Ring in modern day with many of the scenes taking place in vacant human premises, such as a vacant highrise, an empty school, a discarded quarry and a cut-down forest with a partially built freeway. The Gibichung hall in Götterdämmerung was a representation of the now uninhabited Vittoriale degli Italiani on Lago di Garda built by the poet Gabriele d’Annunzio in the last century and where many lavish parties with his friends took place. Costumes of the gods throughout were lush reminding me of modern-day Japanese fashion art. Elaborate masks were utilized to depict many of the characters. Hunding’s men wore dog masks and acted as a pack of dogs. Fricka was accompanied by two attendants wearing ram’s heads.

Dorst emphasized the objectivity of experiencing the Ring by keeping all of the gods, demi-gods and humans separate. In almost every scene there were humans, often children or young adults interacting realistically with the surroundings, but who were oblivious to the drama taking place among the gods and demi-gods.

Dorst created Götterdämmerung to be a real culmination of the Ring epic. He depicted all of the Ring characters up to that point from Rheingold, Walküre and Siegfried as guests in the Gibichung hall. One could make out among the guests, who were Wotan, Fricka, the Rheinmaidens, Siegmund, Sieglinda, Loge, etc. And in Götterdämmerung even we, the audience, were included! Our shoes were lined up at the front of the stage before the Gibichung hall. The real Rheinmaidens, when they appeared at the beginning of Act III, carried mirrors, reflecting us in the audience.

The ending of the Ring can sometimes be a letdown and is often controversial. In this production the fire in the hall is intense (with the guest representing Loge being the last to flee!) burning up the worlds of the gods and demi-gods. The denouement was left for the humans in the real world. A young couple with a bike pass through the surroundings. They stop. The young woman offers her partner a cup of water from a thermos – just like Sieglinde offering Siegmund a cup of water; just like Arabella offering Mandryka a cup of water…. The real world and real life continue on.

Of course, the blend of voice and orchestra in the famed Festspielhaus is unsurpassed. The singing overall was good, but as in all Ring productions there were inconsistencies. Outstanding was the Sieglinde, Eva-Maria Westbroek from the Netherlands. Watch for her as a Brünnhilde in 10 years time. Stephen Gould as Siegfried and Linda Watson as Brünnhilde were memorable. The conductor, Christian Thieleman, had the orchestra playing louder than many conductors would have done leaving one with the impression that he was not as sensitive to the needs of singers as an opera conductor should be.

Tristan & Isolde, August 2008

Jukka Rasilainen as Kurwenal attending the dying Tristan (Robert Dean Smith).

Tristan & Isolde is normally the most sensuous opera staged today, however this production by Christoph Marthaler was anything but passionate. It was weird, bizarre, comic and absurd. With the production of the Ring separating out the lives and drama of the gods and humans, was this a separation of a drama among robots with autistic characteristics (i.e., Tristan and Isolde) and humans represented by the observer, Kurvenal, Tristan’s loyal companion? The time period of this production spans the 1920’s to the 1950’s as depicted in Isolde’s costumes from Act I to Act III, yet Kurvenal is the only character who ages throughout. The other characters are unchanged as if they were not real. The only contact among the characters was occasionally with the hands– even eye contact was nonexistent. Is this not what one would expect with interacting automatons?

All of the action, or in this case, non-action takes place on a ship with three levels. Act I is in a room on the main deck, Act II on a lower deck and Act III in the hull of the ship. So the mechanical characters remained in the same mechanical setting for the entire drama.

The singing and diction of Robert Dean Smith as Tristan and Robert Holl as König Marke were superb, while the Swedish soprano, Iréne Theorin as Isolde was totally unintelligible.

One music critic called this production an example of current German music theater, but I am not sure it could be called a good or even mediocre example of music theater in Germany today. It was certainly not an opera to which the audience could respond with all of their senses. Nor is it a production I would care to see again.

Der Meistersinger von Nürnberg, August 2008

![]()

Katharina Wagner's production of Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg. Photo from 2009: Enrico Nawrath

What an absolute delight to see!! This controversial production of the Meistersinger is by Katharina Wagner, the 29 year old great-granddaughter of Richard Wagner, who is also now the new Co-director of the Wagner Festival in Bayreuth. In this production she remains true to the music and text as originally written, but places the opera in an entirely different context. Rather than a singing competition, it is set in the world of painting and art. Hans Sachs, sung by Franz Hawlata, is a barefoot poet/artist rather than a master shoemaker. Before the final competition, Katharina pokes fun at previous artists/poets/composers, Richard Wagner being one of them. These, depicted by actors wearing grotesque caricatured masks, must be, and were, disposed of before a new world of art can result. However, as is so typical today, as soon as Walther von Stolzing (Klaus Florian Vogt) wins the contest, a promotional contract is signed and off he goes to commercialize his art, leaving the Beckmessers of the world to carry on in the art world. In fact, in this production it is Sixtus Beckmesser (Michael Volle) remaining true to his art, who is the real hero.

This production, which opened last summer, was not appreciated by many critics and members of the audience. However, a surprising number did like it. One opera goer commented that if this is an example of Katharina Wagner’s creativity, then she had her support as the new Co-director of the Festival. We await future new productions under her helm.

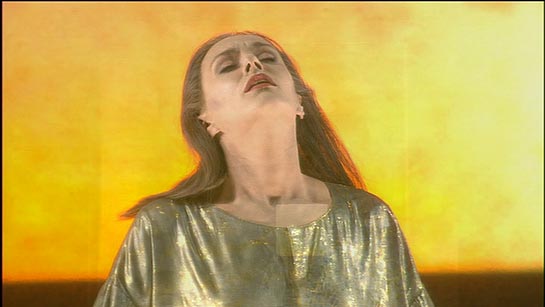

Parsifal, August 2008

![]()

Act 3 of Stefan Herheim's production of Parsifal.

Photo from 2009: Enrico Nawrath

This is the opera that was written specifically for performing in the Festpielhaus. It was beautifully sung with absolutely perfect balance with the orchestra led by Daniele Gatti. In this fascinating production with very elaborate staging the Norwegian Director, Stefan Herheim, used Parsifal and the search for the Holy Grail as a metaphor for the development of Germany as a nation up to the present day. This interpretation was extremely effective.

Act I set in the 1880s depicts the birth of Germany as a nation with the birth of an innocent Parsifal. Christianity was an important aspect in the formation of Germany and this scene exudes Christian symbolism with angels, a Christ figure (Amfortas sung by Detlef Roth) religious rituals, etc. It ends with a rise in German nationalism and the beginning of World War I.

![]()

Parsifal (Christopher Ventris) with the swan he has shot. The swan is Parsifal as a boy. Gurnemanz (Kwangchul Youn) is appalled.

Act II opens with a country bewildered, in poverty and in need of healing as it was after the first World War. Germany in the 1920s and 30s was ripe for an increase in decadence as represented by an androgenous Klingsor (Thomas Jesatko) and Zaubermädchen, who sometimes were depicted as nurses and at other times chorus girls. Kundry, beautifully sung by Mihoko Fujimura, looked like Marlene Dietrich’s famous Blue Angel from the 1930s. The rise of Nazism with its promises of love, honor and protection of the German culture and the beginning of World War II end the second act.

As Act III opens the war has ended and the country is in shambles. Kundry and Gurnamanz (Kwangchul Youn), depicting the surviving German populace, are devastated, but are still there to serve and rebuild. Parsifal, sung by Christopher Ventris, as the redeemer heals Amfortas’ wound. Titurel (Diógenes Randes) and the old order finally die. The staging then moves to the Bundestag where the new government is formed. The opera ends with a giant mirror on stage reflecting the well-dressed affluent audience and present day Germany.

This interpretation by Herheim worked beautifully and was very emotional to experience. Why did it take a non-German like Herheim to use Parsifal as a metaphor for Germany in this manner?

This production also marked the end of an era. Wolfgang Wagner, who had been with the Festspiel for 58 years, 42 of which were as the sole Director, was stepping down. He joined the singers on stage for bows and a standing ovation from a very appreciative audience.

Diana Herbst, October, 2008

Colin Bayliss • Clemens Bieber • Bea and Alec Bobotek • Stephen Charitan • Gary Campbell • Jerry Floyd • Sam Goodyear • Janette Griffiths • Diana Herbst • Hildegaard Arnold Kiel • Randall G. Malmstrom • Anne Midgette • Walter Meyer • Wouter de Moor • John F. Runciman • Per-Erik Skramstad • Brian Slater • Julia Thornton • Natalie Tsang • Mark Twain •

Never the same way since

Bayreuth is far more than the sum of its parts. When I first went as a young and rather green opera critic, excited but a little daunted at the prospect of seeing six Wagner operas in seven days, I expected it to be a rather intellectual week that would be, on some level, good for me. I expected the musical standards would be a lot better than I found them. I didn’t expect that it would be a week of pure fun.

I drove up from Munich (where I then lived) and arrived at the cheapest pension I had been able to locate, only to find that it was filled with other critics from all over Europe operating on similarly restricted travel budgets. With its bare wood floors, modest furnishings, and communal breakfasts, the building was like a dorm at summer camp, except that the other campers were all male, generally older than I, and happy to talk to me all day about Wagner in English, French, and German. In short: I immediately started to have a great time.

Bayreuth represented a sea change in my relationship with Wagner’s operas. I had seen all of them live at that point, had listened to recordings for hours, had loved many of them, and had, I think, in some way fundamentally failed to understand them – to understand, particularly, the way that they require you to give yourself over to them. The way to see Wagner is to focus your whole day on Wagner. A leisurely breakfast, a stroll through town or excursion to some local destination (I was, at the time, inflamed with enthusiasm for Wilhelmine of Bayreuth, and still vow I’ll write a book about her some day), a bite of lunch, and it was time to start dressing for the four o’clock curtain. Wagner doesn’t even seem long if you have no other distractions; the operas are the perfect length when they begin in the late afternoon and you have an hour between each act to digest what you’ve heard, eat, talk, or wander among the crowds of people in evening wear hoisting huge beer mugs (this is, after all, Bavaria) on the grounds.

Together with my colleagues, I smirked at the obsessive passion of the die-hard Wagnerians, like the Frenchman who took violent exception to the criticisms a French colleague and I, thinking ourselves protected by our choice of language, were making about Siegfried Jerusalem’s “Tristan” during intermission (“Do you know how hard that role is to sing?!” “Perhaps,” my colleague remarked drily after the infuriated man had retreated, “but when I come to Bayreuth, I still expect to hear it sung well”). As a foreigner, I wasn’t as bothered as some of my German friends by the old-line, right-wing aura hovering over much of the audience – I simply wasn’t as attuned to it as they were. And I was perfectly aware that the productions – this was the year of the Alfred Kirchner “Ring” and the new Wolfgang Wagner “Meistersinger” (in which I heard Renée Fleming for the first time) – were only so-so. So you can only attribute the magic to the music, which works in spite of everything. I emerged from that week of total immersion with a mad, genuine, and abiding love of Wagner. I have never heard the operas in quite the same way since.

First published on Anne Midgette's blog The Classical Beat

Colin Bayliss • Clemens Bieber • Bea and Alec Bobotek • Stephen Charitan • Gary Campbell • Jerry Floyd • Sam Goodyear • Janette Griffiths • Diana Herbst • Hildegaard Arnold Kiel • Randall G. Malmstrom • Anne Midgette • Walter Meyer • Wouter de Moor • John F. Runciman • Per-Erik Skramstad • Brian Slater • Julia Thornton • Natalie Tsang • Mark Twain •

Bayreuth 2011

After a career in the medical profession, where holidays had to be booked 12 months in advance, retirement suddenly opened up a Pandora's box of operatic possibilties.

Where better than to start at the top of the operatic mountain (my other passion), so it was to Bayreuth that I was to go but alas the chance of such a mere novice obtaining tickets was impossible so when I was not allocated any tickets my plan was hatched.

Flights at that time from Manchester to Munich were so cheap I booked two weekends during the Festival (£35 return) and waited until just before the Festival opened. I was to travel up from Bregenz, having seen Andre Chenier the previous evening, but the train arrival time prevented my joining the queue for returned tickets.

I hoped that a phone call to the booking office might just locate just one ticket on either of the weekends I had booked.

Joy of joy, Frau Benker offered me two tickets, one for the opening night of the 2011 Tannhauser (I am still trying to understand the concept) and for the following night to see Die Meistersinger. Having changed suits on the train from Munich I felt rather conspicious walking onto such hallowed ground and though dressed appropriately, the cloakroom lady was taken aback to be asked to store my trolley case.

And so to the 'Gods' we climbed but I was on the front row and, surrounded by ladies of all ages in gorgeous long gowns, we waited in reverential silence as the lights dimmed. The opening bars of Tannhauser were magic and the magic lasted until the very last note. Such a 'different' production was not going to please all but the booing next to me was by far outweighed by the rapturous applause and footstamping of those behind and below me.

The weather was perfect and before the performance we were 'entertained' by the arrival of the rich and famous and in the intervals the restaurants had a huge variety of tasty food in a relaxing atmosphere under the summer's evening sun.

It was a magical trip which included a more traditional Meistersinger the following evening and the next a flight back home to Manchester with Wagner ringing in my ears.

What a glorious start to retirement - I will return.

Colin Bayliss • Clemens Bieber • Bea and Alec Bobotek • Stephen Charitan • Gary Campbell • Jerry Floyd • Sam Goodyear • Janette Griffiths • Diana Herbst • Hildegaard Arnold Kiel • Randall G. Malmstrom • Anne Midgette • Walter Meyer • Wouter de Moor • John F. Runciman • Per-Erik Skramstad • Brian Slater • Julia Thornton • Natalie Tsang • Mark Twain •

Wagner's entire Ring Cycle live, on stage in Bayreuth

Siegfried and Mime, Act 1 of Siegfried. Photo Enrico Nawrath

My lifelong wish, to experience Richard Wagner's entire Ring Cycle live, on stage in Bayreuth, was granted this year!

I will forever treasure this unique experience!