Parsifal 2023 (Jay Scheib, Bayreuth Festival)

Augmented Reality, Allegory, and Environmental Themes: Jay Scheib’s Parsifal Production at Bayreuth 2023

Andreas Schager (Parsifal) and Elīna Garanča (Kundry). Photo: Enrico Nawrath/Bayreuth Festival

A new Parsifal at Bayreuth always has the air of being a special occasion. Too special, some might say, with the line between going to see a work about religion and participation in a religious ceremony long known to be a blurry one for some of the Wagnerian faithful. And although most people clap after Act I of everyone’s favourite Bühnenweihfestspiel these days, one can’t help but feel that piety may be increasing in some circles around the festival as whole. After all, rumours surrounding the decision to provide only 15% of seats with the Augmented Reality (AR) glasses required for this year’s new production certainly lent the impression that some veteran Grail Knights may unwittingly be mistaking “the composer’s intentions” for a holy spear, and Katharina Wagner for Klingsor. Neither, of course, bear a resemblance, and I will only add that my admiration for Katharina’s unwavering commitment to trying new things at the festival grows each year.

Commitment to artistic innovation does not, however, guarantee that the innovation is an artistic success; and while I very much wanted to like director Jay Scheib’s new production, and was fortunate enough to secure the AR glasses necessary to experience it in full, unfortunately, I ultimately felt that despite some promising conceptual elements, this was a staging that tried to do too much, and consequently ended up saying too little.

Augmented Reality in Jay Scheib's production of Parsifal, Bayreuth Festival 2023. Photo: Enrico Nawrath/Bayreuth Festival

Perhaps the most obvious place to start is with the overall AR experience. Aesthetically, I didn’t mind, even quite liked, the slightly retro look of the images generated (for UK readers of a certain age, think Knightmare). The main problem was that there was simply a hell of a lot going on through the glasses nearly all of the time, and while there were moments where the AR made a positive emotional impact, more often than not the sheer number or size of things being depicted meant that they were merely distracting or obscuring rather than intriguing or enlightening. Often, a dozen or more images of the same symbol, such as a flower, would float around for several minutes, making it hard to focus on the action taking place upon it. At others, single large objects meant that one had to remove the glasses to unblock what was happening on the stage, for example, when two large skulls dominated the proceedings during the opening scene of Act 2, or when a tree appeared in front of the video screen that was magnifying Kundry’s attempted seduction of Parsifal. By the middle of the evening, I therefore found myself moving the glasses up and down like a man doing a bad Eric Morecambe impression in an effort to see both what was on stage and what was in the AR.

The extent to which the AR was used by Scheib to, in his own words, “present [these] worlds in a way that can’t otherwise be conceived” also seemed variable. Some of what was shown served merely to emphasise what was already happening on stage, such a spearhead flying towards us when the physical spear was reclaimed from Klingsor. At other times, AR symbols such as books, minerals, and trees, were not on stage, but easily could have been and made the same point. The fact that there was so much AR at times when there perhaps needn’t have been, also made it all the more perplexing that many of the big metaphysical moments of the piece in which one might imagine AR could really come into its own – the Transformation Music, most obviously – were the few times when little or nothing was done with it. I don’t need to see an AR spear when people talk about a spear, but I’d have loved to have seen Scheib have a crack at a 3D, visual representation of time becoming space.

Having said all that, I do want to emphasise that I am not against the use of AR in principle, in this or any other production in the future. As stated above, there were occasions where I felt it added to the experience, such as when it placed us in a simple starry sky during the Vorspiel, or the impressive, suitably shocking blue shards of electricity that filled the Festspielhaus when the Grail was revealed. At these times the AR did help to make one feel enveloped more fully in the action, and able to see and feel things in a more visceral way than, say, a video projection could do. But I do believe that a much less busy approach overall, coupled with a reduction in its use merely for signposting, would increase its effectiveness enormously.

Jay Scheib's production of Parsifal, Bayreuth Festival 2023. Photo: Enrico Nawrath/Bayreuth Festival

What of the actual theatrical interpretation of the work then? Much like the use of the AR, there seemed to me on the one hand, a lot going on in terms of the number of thematic ideas introduced, but on the other, a lack of focus on any of them enough to really deliver a satisfying, unified production. The clearest strand of the production was that of environmentalism, specifically, the damage caused by the mining of metals such as lithium and cobalt for use in products that are sometimes treated as a panacea for combating climate change. The first scene took place beside a grey metal “tree”, almost Wieland Wagner-esque in its starkness, implying a world in which nature and metals had somehow been conflated. The faith and reverence placed in mined substances were progressively highlighted: first when the balsam Kundry brings for Amfortas seemed to be a chunk of mineral ore; then via the AR when images of similar rock appeared as Gurnemanz sang “Dem Heiltum baute er das Heiligtum”; and later when a blue crystal was shown during the words “…wird nun der Gral dich tränken und speisen.” Unsurprisingly by this point, the Grail was then revealed to be a physical blue crystal, over which blood from Amfortas’ wound was poured, before it was then drunk by both Amfortas and Titurel. An allegory for the human and environmental costs the world accepts during the mining of metals for St. Elon of Tesla in places like the Democratic Republic of Congo? Quite possibly.

Just as I wrote last year in reference to Valentin Schwarz’s Ring, I don’t think an environmentalist angle is necessarily a bad starting point for a production of Parsifal either, given its themes of compassion, redemption, nature, etc. Indeed, one might say that the problem of overconsumption in the West might be solved if we were all to engage in a little more denial of the Will when it comes to material, if not sexual, temptation. Would Act 2 follow through on these lines? Well, sort of. Expansion of the mining theme was, disappointingly, almost entirely absent for most of the second act, which played out pretty straight up until Parsifal picked up a piece of mineral ore in one hand (while holding a dead man’s heart in the other) when he sang “Nein! Nicht die Wunde ist es.” Perhaps this could work if the director went all-in on this not being a first kiss, but a first iPhone, yet the straightforward presentation of the seduction up until this point did not seem to align with that sort of reading, especially given some of the other themes introduced by Scheib that we will discuss later.

The environmental message did return more strongly in Act 3, in which, if anything, it rather lacked for subtlety. AR plastic bags, bottles and batteries were strewn about in front of a set filled with mining equipment, while AK-47s also appeared, presumably to highlight that the mining taking place had been of so-called “conflict minerals”. Flowers and electrical components were visible in equal measure during the Good Friday scene, before the evening culminated in Parsifal revealing the crystal Grail and smashing it on the floor.

A total rejection of technological solutions to climate change? That seemed to be the message, although it was not clear how environmentalism, if that were the production’s “redeemer”, would be redeemed beyond this, as Parsifal seemed to be providing no alternative. It may be the case that digging up metals for electric cars is not the answer, but surely simply doing nothing is not the answer either.

There did, however, seem to be an attempt to redeem something at the end of the production – sexual love – in the culmination of a theme that competed for prominence with the environmentalist strand throughout the evening.

This redemption of love was confusing both in its set up and resolution. It was introduced in the Vorspiel when Gurnemanz was seen in a passionate embrace with an unknown woman, before seeming to feel guilty about the liaison and back away from it. As the evening progressed, we would realise that this woman was not quite Kundry, but a sort of double played by another actress. Who or what was she supposed to represent? The concept of sensuality? The uncursed Kundry? The female sex? Mother nature? Herzeleide? All seemed possible at different times, but I remain unsure. In any case, she often appeared on stage at the same time as Kundry, and either carried out actions, or simply observed proceedings, in silence. Occasions on which she appeared included: Parsifal talking about how he had a mother; the opening scene of Act 2; and nearly all of Act 3 where she was seen collecting flowers and shadowing the baptism of the “real” Kundry. As the final bars played, she approached Gurnemanz and hugged him, the hermit now apparently content to show his feelings for her.

If one wished to give the benefit of the doubt to Scheib and his team, one might think that they were deliberately attempting an anti-Schopenhauerian interpretation of the work, however wise that may or may not be. After all, the smashing of the Grail is nothing if not a firm rejection of Schopenhauerian cyclicality, with social change and progression after the curtain falls almost guaranteed by this staging. Adding to this a rehabilitation of giving in to desire, about as anti-Schopenhauerian as one can get, and one could reasonably surmise that Scheib thought he owed the world a Tannhäuser and was attempting to point us to the remnants of Wagner’s Young Hegelian youth within the work. However, given the absence of any references to the philosophical influences on Parsifal in the programme notes, the nod to cyclicality given by showing an AR ouroboros during Amfortas’ Grail ceremony monologue, and the aforementioned straightforward presentation of Parsifal recoiling from the kiss, I think assigning this intent is probably a step too far. In any case, as much as I might agree with the message as it pertains to contemporary life, I just don’t think the production did nearly enough to explain how or why Gurnemanz or any other character went on that journey.

Other lines of inquiry were clearly intended to be integral to the concept in addition to these two themes, as evidenced by the programme notes. Several pages are dedicated to highlighting how Kundry is defined by the fears and prejudices of men, and so naturally, one would expect the production to have focused in some way on empowering her, on giving her back some agency somehow. However, even after racking my brain, referring to my notes, and re-reading the programme, I cannot really recall the production doing this at all, with the character more or less doing everything in the manner one would expect of her in a “standard” production of Parsifal. Similarly, two pages of the programme notes are devoted to discussing the concept of memory, and how Parsifal’s is shaky. Other than him wearing a t-shirt with “Remember Me” on the back, exploration of this theme and any insight to be gleaned from it was also hard to discern. On the other hand, there were plenty of little titbits here and there not seemingly connected to the obvious themes that raised more questions: the gold religious relics also brought on stage that were not destroyed with the grail, for example, or the AR burning bush that could perhaps have been both an environmental message and a reference to the biblical story. With such a potpourri approach though, it became impossible to fit them all into a broader concept.

Georg Zeppenfeld in Jay Scheib's production of Parsifal, Bayreuth Festival 2023. Photo: Enrico Nawrath/Bayreuth Festival

Still, even if the directorial side of the evening proved frustrating, things were much better on the musical side. In the pit, there was much to like about Pablo Heras-Casado’s reading of the score. If the first act were a little on the fast side at times for my taste, what we may have lost there in mystical grandeur we made up for in spades during the more dramatic music of Act 2, which was taught, thrilling, and moving in equal parts. Above all, fluency was never lost, and the “Bayreuth Parsifal” sound was always there.

Singing wise, the two standout performers were Andreas Schager in the title role, and Elīna Garanča as Kundry. Schager is a known quantity by this point, and remains as indefatigable as ever, stepping into this role at short notice despite also being down to sing both Siegfrieds. The power was, of course, always there to be called upon, and was deployed thoughtfully, while his soft singing and dramatic commitment were equally impressive. Garanča, meanwhile, gave us a Waltraud Meier-esque acting performance in which every facial expression and hand movement was done for a reason, coupled with singing that was variously tender and beautiful, dramatic and powerful. She justly received the largest ovation of the night, and the combination of her, Schager and Heras-Casado made the second half of Act 2 the highlight of the evening.

Georg Zeppenfeld (Gurnemanz) and Andreas Schager (Parsifal) in Jay Scheib's production of Parsifal, Bayreuth Festival 2023. Photo: Enrico Nawrath/Bayreuth Festival

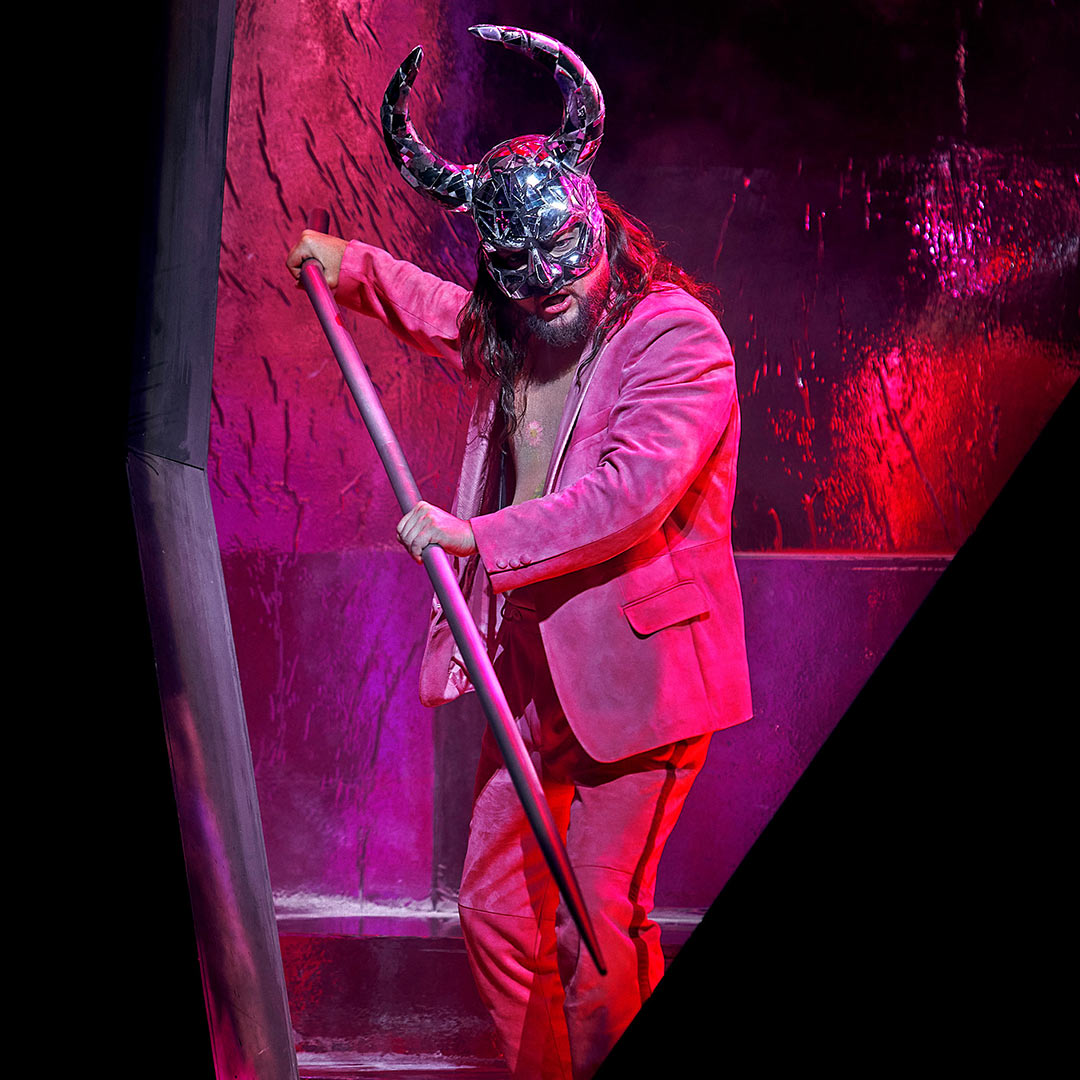

As Gurnemanz, Georg Zeppenfeld, rivalling Schager these days as the opera world’s most ubiquitous superstar, once more reminded us that he is the absolute King of Diction in a typically thoughtful portrayal, while Derek Welton brought a rich tone and attention to the text to what was a notably physically robust portrayal of Amfortas. Elsewhere, Jordan Shanahan was appropriately menacing as Klingsor, Tobias Kehrer took his cameo as Titurel well, and all the knights, squires and flowermaidens sung to a consistently high standard.

Jordan Shanahan (Klingsor) in Jay Scheib's production of Parsifal, Bayreuth Festival 2023. Photo: Enrico Nawrath/Bayreuth Festival

So, all in all, a production that threw the kitchen sink at the work, and as a result, spread its directorial resources – and our attention – too thin to really hit any home runs with any of the points it wanted to make. I should note, though, that Scheib speaks enthusiastically about the opportunities that the “Bayreuth Werkstatt” provides in terms of “continual reinvention”, so I have some hope that over the course of its run, a more refined version will emerge. And even if it doesn’t, the attempt should be applauded.

The flowermaidens in Jay Scheib's production of Parsifal, Bayreuth Festival 2023. Photo: Enrico Nawrath/Bayreuth Festival

Conductor: Pablo Heras-Casado

Director: Jay Scheib

Stage design: Mimi Lien

Costumes: Meentje Nielsen

Video: Joshua Higgason

Chorus master: Eberhard Friedrich

Amfortas: Derek Welton

Titurel: Tobias Kehrer

Gurnemanz: Georg Zeppenfeld

Parsifal: Andreas Schager

Klingsor: Jordan Shanahan

Kundry: Elīna Garanča / Ekaterina Gubanova

1. Gralsritter: Siyabonga Maqungo

2. Gralsritter: Jens-Erik Aasbø

1. Knappe: Betsy Horne

2. Knappe: Margaret Plummer

3. Knappe: Jorge Rodríguez-Norton

4. Knappe: Garrie Davislim

Klingsors Zaubermädchen: Evelin Novak, Camille Schnoor, Margaret Plummer, Julia Grüter, Betsy Horne, Marie Henriette Reinhold

Altsolo: Marie Henriette Reinhold

Sam Goodyear

Sam Goodyear is an opera fan and Wagner enthusiast, originally from Portsmouth but now living in Germany. He read history at Peterhouse, Cambridge, and has at various times worked as a bookie, translator, trader, journalist, and TV researcher. He currently works in socially responsible investment. While very much an amateur, his interest in music has in the past led to him singing on BBC radio, and playing the trumpet in front of the queen. He attends as much Wagner both at home and abroad as time and money will permit, and he has written on Wagner for Classical Music Magazine.

Parsifal 2023 (Bayreuth Festival) - Reviews and background

For the first time in Bayreuth, a production made use of AR glasses to give the audiences an augmented reality experience.

Reviews

Augmented reality-infused production of Wagner’s `Parsifal’ opens Bayreuth Festival (By RONALD BLUM, Associated Press): ‘AR use was at times visually busy: insects and starbursts appeared tangential to the action, and there were a few instances of slight judder. Many digital visuals were impactful, such as arrows shot at the audience. A spear through an ear referenced Hieronymus Bosch’s “The Garden of Earthly Delights.”’

Background

Screenshot from Bayreuth Festival AR introduction video

Conductor: Pablo Heras-Casado

Director: Jay Scheib

Stage design: Mimi Lien

Costumes: Meentje Nielsen

Video: Joshua Higgason

Chorus master: Eberhard Friedrich

Amfortas: Derek Welton

Titurel: Tobias Kehrer

Gurnemanz: Georg Zeppenfeld

Parsifal: Andreas Schager

Klingsor: Jordan Shanahan

Kundry: Elīna Garanča / Ekaterina Gubanova

1. Gralsritter: Siyabonga Maqungo

2. Gralsritter: Jens-Erik Aasbø

1. Knappe: Betsy Horne

2. Knappe: Margaret Plummer

3. Knappe: Jorge Rodríguez-Norton

4. Knappe: Garrie Davislim

Klingsors Zaubermädchen: Evelin Novak, Camille Schnoor, Margaret Plummer, Julia Grüter, Betsy Horne, Marie Henriette Reinhold

Altsolo: Marie Henriette Reinhold

Reviews by Sam Goodyear

Stefan Herheim's production of Der Ring des Nibelungen at Deutsche Oper Berlin (2024)

Roland Schwab: Tristan und Isolde (Bayreuth 2023)

Jay Scheib: Parsifal (Bayreuth Festival, 2023)

Tcherniakov: Das Rheingold, Staatsoper Berlin

Tcherniakov: Die Walküre, Staatsoper Berlin

Tcherniakov: Siegfried, Staatsoper Berlin

Tcherniakov: Götterdämmerung, Staatsoper Berlin

Bayreuth Festival 2017: Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg (Kosky/Jordan)

Bayreuth Festival 2015: Tristan und Isolde