Dmitri Tcherniakov: Der Ring des Nibelungen, Siegfried - Staatsoper unter den Linden, Berlin, 2022

Tcherniakov: Siegfried, Staatsoper Berlin

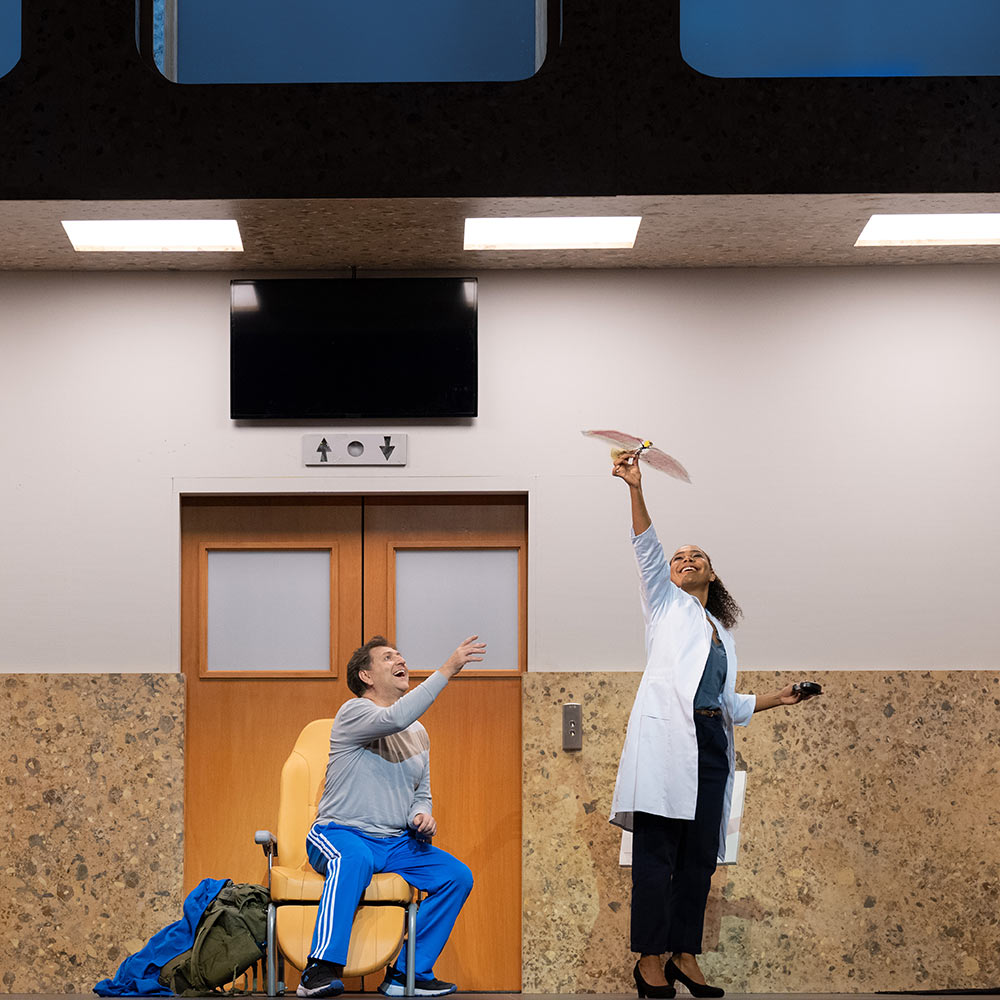

Andreas Schager (Siegfried) and Victoria Randem (Der Waldvogel) Photo: Monika Rittershaus

There is a moment in the final episode of Star Trek: The Next Generation when, referencing his judgment of humanity, the omnipotent being Q tells Captain Picard that “the trial never ends”. Whether this is an intended message of Dmitri Tcherniakov’s Ring cycle or not, it was something that came to mind following this production of Siegfried, the ending to which seemed to make it clear that despite Wotan’s predicament, the series of experiments we had seen being carried out on the main players, and his attempts to control them, were far from winding down.

For the third night in a row, we opened with a video, this time of a young child. The child, appearing dishevelled, sad, and frightened, was surrounded by large Lego-style toys that we would soon see again in the bedroom of Siegfried. With Mime’s dwelling as a whole being a redecorated version of Hunding’s hut from Die Walküre, the impression that the lab equipment had merely been reset for a new test was firmly given, and then reinforced by the appearance of the Wanderer behind the secret window, watching on as Siegfried inquired about his father and mother.

Michael Volle (Der Wanderer) and Anna Kissjudit (Erda) Photo: Monika Rittershaus

If Siegfried, like his parents, had been born to be a guinea pig (or a rabbit), there were hints throughout Act 1 that he might be somewhat aware of this, or at least know something fishy was going on. Futile attempts to see what was on the other side of the window preceded a finale in which, having literally smashed or set fire to everything associated with his childhood, he pointed to the Wanderer, now revealed to him behind the glass. That the bear at the start of the opera was Siegfried himself in a bear suit, but one that appeared to have Wotan’s head, was also intriguing, if rather confusing. Was it Siegfried confronting Mime with his biggest fear – the man behind the experiment? Whatever the case there, the idea that much of what we had seen throughout the cycle was merely a representation of the state of mind of different characters also returned, due to the fact that Nothung was never reforged. In this instance, any symbolic shift of power happened not through the creation of something new, but purely through a changed mental attitude to the old.

While Act 1 continued from where we left in Die Walküre in terms of a relatively light-handed depiction of the participants being under scientific observation, the more explicit experimentation of Das Rheingold returned with a vengeance in Act 2, which began with a message that an experiment would begin in 30 minutes time. That trial would start with the arrival of Siegfried and Mime, and follow six phases explicitly named to us:

- Phase 1 – Relaxation (Forest Murmurs)

- Phase 2 – Immersion in Meditation

- Phase 3 – Search for the Inner Helper

- Phase 4 – Contacting the Inner Helper

- Phase 5 – Confrontation with Conflict. Reaction to Danger.

- Phase 6 – Realisation of an Unconscious Desire

The first two phases – the preparation of the subject for the test, one might say – took us through Siegfried’s musings on his mother and whether all mothers die in childbirth, up to the entrance of the Woodbird, another institute employee in a white coat, at the beginning of “Phase 3”. Here, and in the following phase, she seemed to be providing stimulus in order to analyse his reactions to it, first with a toy bird, and then with pictures of pipes and horns.

Apparently content with his responses, she left, at which point Fafner was brought in for the start of “Phase 5”, now no longer a quasi-gangster in a long leather coat, but a mental patient in a straight jacket. Had he always been an inpatient, even in Das Rheingold, but merely living out a fantasy role planted in his head somehow by Wotan and Loge? I’ve tried to think of another explanation, but cannot reconcile one with him seemingly being firmly under the control of Wotan and his institute at this point in the cycle. The eerily artificial nature of what we were seeing then continued, Siegfried stabbing the giant with his still-broken sword (with the Wanderer once more watching things unfold), before having the Tarnhelm simply given to him by the Woodbird, almost like a dentist giving a lollipop to a child as a reward for sitting still during a filling. Throughout the entire act, the stage revolved from room to room, the characters walking through them in the same direction like a dog chasing its tail. The cyclical nature of life, death, and rebirth? Perhaps.

Meanwhile, we had left Wotan at the end of the previous opera as a rather defeated character, his failed experiments having apparently caused cracks in his own mentality. But though older and past his physical best, his cool observation in the first two acts of this work made it appear that he had had something of second wind psychologically in the intervening period. In Act 3, it became clear he was certainly still in charge of the institute too, as evidenced by his ability to dismiss employees from the conference room before his meeting with Erda.

Would this scene be the point, as one might expect, when he finally gives up his experiments, resigns from the institute, and no longer attempt to direct events? In a word, no. Despite a typically vociferous declaration of his will for the end of the Gods, we immediately transitioned to a situation in which the Woodbird knocked on the door to check if the doctor was ready for his patient, before ushering Siegfried in to see him. A spear was broken, but it was seemingly all just for show and done by the Wanderer himself.

Was this enough for us to infer an ongoing attempt by him “zu hemmen ein rollendes Rad”? Perhaps not, but even if his will was for the wheel to keep turning in its current direction, the final scene made it clear that at the very least, he was still determined to be the one doing the turning. A “Sleep Laboratory” was, perhaps unsurprisingly, the location. What was surprising was seeing Brünnhilde, still exhibiting the childlike mentality with which she had ended the previous opera, being led into the room by her father, cuddly-toy Grane in hand, in order to play a game of Sleeping Beauty. Fire and shields drawn playfully on walls, and much laughter, accompanied the love duet, the pair very much continuing some sort of make believe. As the final words were sung, the Wanderer was still watching, only to exit at the sight of the Norns.

Johannes Martin Kränzle (Alberich) Photo: Monika Rittershaus

Turning to the music, Christian Thielemann continued his relatively expansive interpretation of the previous evenings, always maintaining a sense of where we were headed. If overall slower tempi led to the end of Act 1 having less pure excitement than it sometimes can, his use of rubato and rallentando brought a different, more epic sense of drama to the action that one does not typically hear today. Additionally, he coaxed some truly beautiful sounds out of the Staatskapelle Berlin, with some of the string playing in quieter sections of Brünnhilde’s awakening sounding almost ghostly.

In the title role, Andreas Schager demonstrated once again that he is the Siegfried de nos jours, in an indefatigable performance that not only surpassed the one I saw from him in Bayreuth earlier this summer, but that was perhaps the best I have ever seen from him in this role. The hints of tiredness that I detected in August were nowhere to be seen, his high notes as sustained and powerful at the end as they were at the start, despite the slower tempi. Moreover, this was no mere showcase for his power, with the gentler passages, particularly in Act 2, sung with an eye-opening lightness, tenderness, and lyricism.

Stephan Rügamer was a fine Mime, the voice bright and characterful but not exaggeratedly so, something which could also be said about his acting performance. Johannes Martin Kränzle was also splendid as his brother Alberich, convincing as an older version of the character both vocally and physically, and indeed, their moments together had a certain Abe Simpson vs Jasper quality that worked well.

I have little to add to my previous reviews about Michael Volle, but suffice it to say his Wanderer was as expertly crafted as his younger Wotans. Anja Kampe gave us plenty of drama as Brünnhilde, and if some passages (e.g. “Ewig war ich…”) could perhaps have been handled slightly more with kid gloves, we were nevertheless handsomely compensated with strong characterisation and an ability to match Schager in the power department when necessary. Meanwhile, Peter Rose improved upon his Rheingold Fafner in a solid performance, Anna Kissjudit continued to show an impressive fullness of tone as Erda, and Victoria Randem handled the Waldvogel’s coloratura with ease and beauty.

At the end of the third evening then, Tcherniakov has presented us with a world in which the ring appears to be broadly associated with the power of the mind, and perhaps its potential to supersede or dictate reality. Alberich is still convinced of his ability to regain the upper hand, despite being barely able to walk; Fafner and Brünnhilde were or are apparently suffering from delusions; while Siegfried’s development seemed to be as much about the way he came to think about and react to his surroundings than anything else. Through all of this, Wotan continues to pull the levers, raising the question of how much his character has really learned or changed due to events. What I am perhaps beginning to yearn for at this stage is a bit more of a sense of what Tcherniakov is trying to say with all of this, as the production remains rather inscrutable in terms of a “message”, if such a thing is important, and the series of experiments being carried out on the character is certainly a challenge to understand in a purely narrative sense. There’s still four and a half hours until the experiment ends though, of course. Or maybe it won’t…

→ Tcherniakov: Das Rheingold, Staatsoper Berlin, 2022

→ Tcherniakov: Die Walküre, Staatsoper Berlin, 2022

→ Tcherniakov: Siegfried, Staatsoper Berlin, 2022

→ Tcherniakov: Götterdämmerung, Staatsoper Berlin, 2022

More reviews of Dmitri Tcherniakov’s Ring production at Staatsoper Berlin

Das Rheingold

The Rheingold Experiment: Tcherniakov’s new Ring des Nibelungen at the Staatsoper Berlin (Alexandra Richter, bachtrack.com)

Mark Berry: Berlin Festtage (1) - Das Rheingold, Staatsoper Unter den Linden, 4 April 2023

Die Walküre

Mark Berry: Berlin Festtage (2) - Die Walküre, 5 April 2023

Siegfried

Mark Berry: Berlin Festtage (4) - Siegfried, 8 April 2023

Götterdämmerung

Mark Berry: Berlin Festtage (5) - Götterdämmerung, 10 April 2023

Zwei Zimmer, Küche, Bad: Götterdämmerung an der Staatsoper Berlin (Alexandra Richter, bachtrack.com)

The Ring

Review: Berlin Takes Wagner’s Approach to Staging the ‘Ring’. All four parts of Wagner’s epic were presented within a week, in a new production by Dmitri Tcherniakov inspired by the work’s experimental roots. (Joshua Barone, The New York Times)

Outstanding performances can’t save Dmitri Tcherniakov’s new production of the Ring – originally due to have been conducted by Daniel Barenboim – from closing to a barrage of boos (Fiona Maddocks, The Observer)