Alexander Meier-Dörzenbach, the dramaturg in Stefan Herheim's production team, on the new La Bohème production in Oslo, on Wagner and Puccini

– There is so much more than mere sentimentality to this great opera

Dein Meister ruft dich, Namenlose: Mimi (Marita Sølberg) controlled by Death in the character of the Drum Major (Svein Erik Sagbråten) in La Bohème, Act 2. The second Act turns into a shocking and grotesque dance macabre with the final image of Death marching away with Mimì.

Foto: Erik Berg / Den Norske Opera

With the new production of Puccini's La Bohème in Oslo Stefan Herheim and his team reaches a new high in terms of innovative reading of a work everyone thought they knew. Herheim's La Bohème is heartbreaking and grotesque; images of death are always present. And everything is in the score and the libretto.

Herheim updates tuberculosis with cancer, and thus more people can relate to the tragedy. We are challenged to deal with our own experiences relating to death. Rodolfo refuses to accept that Mimì is dead. Her death happens in a scene before the actual opera starts. Fantasy blends with reality in this production where the previous, traditional, production of La Bohème in Oslo symbolizes our own (and Rodolfo's) escapism.

As the music starts, Mimì is dead. For four acts she haunts Rodolfo as he is unable to accept his loss.

Wagneropera.net met Alexander Meier-Dörzenbach, the dramaturg in Stefan Herheim's team, to discuss the ideas behind the concept.

Alexander Meier-Dörzenbach, in this production, everything revolves around Mimì's illness and death. And at the center lie the existential question of how to deal with death. The production starts with Rodolfo sitting by Mimì's death bed in a modern hospital (before the music starts). This closely parallels the action during the Prelude of Parsifal Act 1 [in Herheim’s production] when Parsifal's mother Herzeleide is dying, where how to deal with death is also a central theme. Parsifal is also characterized by denial and repression, which, of course, is integrated with the "German history concept". Is there an inner relationship between these two scenes?

It may come as a surprise to you, but we have never thought about that parallel. We came to those images from such different angles and diverse perspectives that the structural similarity of those two openings was never apparent to us. But your observation is valid: During the prelude to Parsifal, the young, naive boy of the 19th century is in denial of his mother's sickness and runs out. As soon as his mother is dead, she turns into some kind of spiritual being, a ghostly entity, which haunts him. In La Bohème, however, we have a very realistic starting point in the here and now of an adult perspective. In our La Bohème we musically start in silence, albeit we have medical sounds. Another difference is of course that in Parsifal – although a psychological reading is part of it – we were also concerned with German history, the reception history of the piece, the myth of Bayreuth etc. so that the psychological layer was just one of many. In our production of La Bohème, however, the psychological level and its mechanisms is at the very center. There is little cultural context to be considered, since it has already been taken away by Giacosa and Illica, who had turned Murger’s novel full of aesthetic discussions and social criticism into the libretto displaying a love story around illness and death. We directly dive into the soul of Rodolfo, a human being who is hurt, who needs to face something we all try to repress – the death of a beloved one – and the psychological mechanism of escaping the reality we dare not face, while in Parsifal, death is merely a door opener to an entire realm of associations, symbols and contexts. In Parsifal it was much more a process of finding images that allowed us to take a new look into one of the greatest works in musical history from different perspectives. In Bohème the task was to take the subject matter – coming to terms with losing a beloved one – seriously and allow the emotionally charged music to reach the soul and the consciousness alike and not drown the piece in sugary superficiality.

Alexander Meier-Dörzenbach was born in Hamburg in 1971 and read American studies, German studies, the theory of education and art history. His doctoral dissertation at Hamburg University was an interdisciplinary study of Gertrude Stein, Sherwood Anderson and modern art. He has worked regularly with Stefan Herheim since the latter's graduate production of Die Zauberflöte, notably on I puritani and Don Giovanni in Essen, Madama Butterfly in Vienna, Giulio Cesare in Oslo, La forza del destino in Berlin and Das Rheingold in Riga and Bergen. He currently teaches American studies at the University of Hamburg, with particular emphasis on American literature, painting and music, and also lectures on dramaturgy at the city's Academy of Applied Sciences, while pursuing a freelance career giving classes on art and culture. He has also worked as dramaturge on Karoline Gruber's production of Ariadne auf Naxos in Leipzig.

Interview with Alexander Meier-Dörzenbach about Lohengrin at Staatsoper Berlin

La Bohème is a work of almost unbearable sentimentality. What were your thoughts on how to deal with this when you prepared the concept?

First of all, we thought we needed to create a distance to that sugary sentimentality in order to have a critical approach to the piece. However, each time we listened to the opera we were taken by that very sentimentality. It is truly heartbreaking every single time you reach the point where Mimì has died and Rodolfo bursts out "Mimì! Mimì!" But there are ways to engulf in this sentimentality and still deal with the effects of their creation from a certain distance. By closely embracing the sentiment, by not being afraid of showing the powerful feelings, we were able to find access to Bohème on an emotional as well as intellectual level. However, there is a difference between just affirming the sentimentality and making its subject matter the core. The moment the opera stops, when Rodolfo has to accept that Mimì is dead, is actually the starting point for us. We take a look at Rodolfo's escapism throughout the entire piece and show how memory, projection, reality and fantasy interact – “chimeras” as they are called by Rodolfo and Mimì in the opera. However, by doing so, we are just unfolding what we find in the score. We want to show how Puccini works with modern harmonies and sometimes even includes cluster-like tone structures. There is so much more than mere sentimentality to this great opera, because you cannot trust this sentimentality, but are always musically reminded by means of contrast that there is another reality to be considered.

Rodolfo: "Oh, how sweet your face looks, its beauty softly kissed by the gentle moonlight. In you, sweet maiden, I see the dreams of love I have dreamt about forever." Mimì's hospital room transformed to a romantic image during the love duet "O soave fanciulla". Foto: Erik Berg / Den Norske Opera.

I must confess I have serious difficulties with the lightheartedness in La Bohème and the rather infantile humour of the Bohemians, especially. What were your thoughts about these comic elements?

In our production this humour has its roots in a distraught situation, Mimì – or rather Lucia – has just died – and there is a constant ambiguity about the ensuing lightheartedness. There are moments of utter desperation and attempts to escape this kind of reality. It is not about the poor "artists" trying to escape their miserable surroundings by means of fantasy. There is a twist in it, they are made into these “artists”. Rodolfo is breaking into a new reality and tries to integrate everyone. So actually, the lightheartedness is a phony one, a desperate way of dealing with grave matters – also in a literal sense.

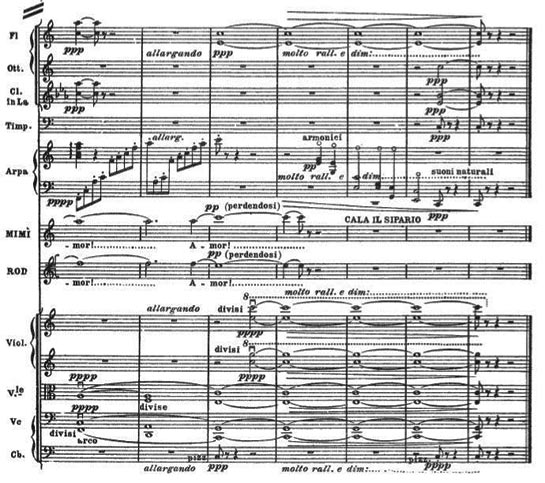

Amor! Amor! Rodolfo singing with a high C or not: In Stefan Herheim's production of La Bohème in Oslo, the lovers leave the stage as nightmarish grotesque characters seep onto the stage, turning to the audience with a macabre smile on their faces: We've got 'em. The love is an illusion, and sooner or later Rodolfo will have to accept that Mimì is dead. (Score showing the end of Act 1. Hover to see image from the ending of Act 1.)

In this production of La Bohème, Rodolfo is the protagonist characterized by his denial and the way he deals with the death of his beloved. His escapism opens up questions about what is fantasy and what is reality. But who is the seamstress Mimì? The simple-minded creature portrayed by Renata Scotto, or the more intelligent, self-aware character, as portrayed by Anna Netrebko?

Apart from the fact that in our production Mimì is not “real” in the conventional sense, but becomes some kind of spiritual remembrance, a kind of ghost-like projection, she plays with the stereotype of being perceived as a naive, beautiful, innocent woman. I think she is playing with the stereotypical idea of womanhood, the “true woman”-ideal of the 19th century. I think of her as a person who is very much aware of two different realms. "Everyone calls me Mimì, but my name is Lucia," she says, and we take this dichotomy to an extreme. The “curioso”-moment at the end of the first act that might be taken as innocently as Scotto does or as coquettish as Netrebko renders it, is of a different nature in our production. We have a beautiful image of Mimì and Rodolfo hovering above the clouds in a star lit sky while the wall opens to the next scene… The curiosity is not about possibly having sex on return, but about love granting life and the discovery that it doesn’t.

Bin ich's? Bist du's? Ist es kein Trug? Ist es kein Traum? Mimì visits Rodolfo as a product of his wishful dreams, memories and repression. It could be a flashback; it certainly is a nightmare. Herheim's universe is a series of questions - the audience has to provide the answers. Foto: Erik Berg / Den Norske Opera.

So basically, Mimì is a projection of Rodolfo's fantasies?

Since we are playing with the 1963 production here in Oslo, the audience actually has a kind of an ideal Mimì, a traditional kind of Zeffirelli-like version. But only after a modern hospital room has opened up and the operatic reality we perceive turns out to be an escapist approach to fly from the horrific reality of death by cancer through memory, fear, wishful projection – all of which we bring to the opera as well – the hope to dive into a world where everything is beautiful and perfect and maybe even kitschy. Although we sometimes cater to those wishes, we also always make it a subject matter that there is a reality we want to escape from through opera.

Mimì (Marita Sølberg). Foto: Erik Berg / Den Norske Opera

One of the trademarks of a Herheim production is that elements in the score are given visual expression on stage. Puccini uses Leitmotifs, albeit in a very different manner than Wagner. In Puccini they function more as signposts, whereas in Wagner you have a complex symphonic development. Actually, this production is brought to life, so to speak, with the Leitmotif of the Bohemians visualized as an attempt to revive Mimì with a defibrillator. You have of course analyzed Wagner's use of Leitmotifs when preparing for Parsifal (Bayreuth), Lohengrin (Berlin), Tannhäuser (Oslo), Das Rheingold (Riga) and the upcoming Meistersinger (Salzburg). I guess the concept of visualizing Leitmotifs in Wagner must be a quite different story than in Puccini's case.

Absolutely. Wagner has a much more intellectually charged idea about Leitmotifs. They develop, they move within the orchestra through different instrumental groups, and there are often complex combinations of Leitmotifs. In Wagner we see a more intricately constructed system of Leitmotifs interweaving several ideas. In Puccini the Leitmotif technique appeals more to an immediate listening. If we were to take a Leitmotif in Wagner and put an image to it and repeat that pattern each time that the Leitmotif appears, we would end up with a rather chaotic mosaic. In Puccini the beauty of the melody is to be considered first, and we have the opportunity to work with certain Leitmotifs by finding images for them, so we might call them visual echoes.

Act 3 of La Bohème as you have never seen it before: Rodolfo (Diego Torre) meets himself in the character of Death (Svein Erik Sagbråten). At this point he is still denying and repressing. On the operating table is Musetta (Jennifer Rowley) "teaches singing to those that stay here". Foto: Erik Berg / Den Norske Opera

In this production the traditional staging of the La Bohème-production that was played in Oslo is used as Rodolfo's (and the audience's) escape from the dreadful reality of facing and accepting death. The Tannhäuser production in Oslo also used elements from an earlier production in Oslo. What is the meaning of this? Is it just play?

Yes and no. It is play, but only if we don't take "play" as meaning something of lesser importance than so-called reality. A “play” always has certain rules and traditions which need to be followed in order for a play to work. We work with traditions and face the conventions and expectations of the audience. And since Stefan Herheim's upbringing was with the Norwegian Opera, he has a very strong visual connection to these productions. None of us in the team started to love opera at a young age in terms of modern German Regietheater, but in terms of very old and traditional ways of telling a story. But that was also a time, when you had three stations on TV, which ended its program before midnight…the level of visual and sensual expectation was quite a different one. However, we want to bring that theatrical sensuality into a refined intellectual perception that allows us to enjoy the beauty of a work and yet not feel that our brains are neglected. So yes, it is play, but a play that demands us to understand the rules by which opera is played and therefore also to understand the rules by which we play within our own reality.

But you have to agree that a lot of opera lovers will be confused and leave the opera house with a multitude of questions after having attended a Herheim production.

Well, isn't it great if people ask these questions? I can assure you that in all our productions there are good answers to each and every one of those questions. We want to irritate in a constructive way so that people start wondering and hopefully grasp that nothing is random, but that there is a very intelligent setup. Gertrude Stein once said when asked about the difficulty of understanding her opaque texts: “If you enjoy you understand if you understand you enjoy. What you mean by understanding is being able to turn it into other words but that is not necessary.“ I think it is wonderful if people ask questions because this means that they are activated. Opera works first of all on a direct level by moving and touching our souls. But the beauty of opera is that it need not stop there. Opera has so much to offer also for the intellect that it is definitely possible to integrate a meta-level albeit creating an illusion – but an illusion, which is always conscious of being an illusion. Opera allows you to be drawn into a fantasy world, but at the same time allows you to reflect upon this. This ambiguous moment of sensually enjoying an illusion and at the same time reflecting upon your enjoyment, reflecting upon the illusion, reflecting upon the construction of this reality makes opera the most unique experience you can have in terms of art.

In several productions you identify a character with the audience. Tannhäuser falling asleep as a member of the audience, for example, or the Pilgrims singing from the auditorium. Or you make a connection between the stage and the auditorium, for instance by lowering a gigantic mirror in front of the audience in Parsifal. Here in La Bohème Rodolfo's denial and desperate escape (into a traditional opera production!) also represents the audience's need for escapism. Can you say more about this identification between Rodolfo and the audience?

I think that has a lot to do with the meta-theatre, that we in the audience realize that we are an integral and vital part of the show. If the fourth wall is broken, there is suddenly a consciousness of the audience when they realize that they are part of the experience. The show is not only made for them but also partly by them. In our Wagner productions we have integrated the audience on a large scale; here in La Bohème it is a much more quiet and voyeuristic mode. We are made aware that we are looking at the most intimate of all human scenes, when someone realizes that his beloved has just passed away. At this moment Rodolfo looks into the audience and we are made aware that we, in a way, are emotionally hungry Peeping Toms. You are right, the audience is always part of the meta level due to the fact that the production is played for the audience. And this is exactly where the production should end and start living in questions: within the audience. Hopefully the visual and auditive images linger much longer than just through the duration of the performance.

The Bohemians joking in Act 4. In the background: Death as the concertmaster and the Peeping Toms (us). Foto: Erik Berg / Den Norske Opera

Stefan Herheim: La Boheme (Oslo) - Selected Reviews

- Martin Nyström (Dagens Nyheter): En ”La bohème” vars såväl sceniska som musikaliska uttryckskraft är i världsklass

- Jörn Florian Fuchs (NMZ): Opulente Oper für eine Krebspatientin: Stefan Herheim inszeniert Puccinis „La Bohème“ in Oslo

- Ragnhild Veire (NRK): La Bohème for voksne

- Magnus Andersson (Ballade): Skjellsettende La Bohème

- Ida Habbestad (Aftenposten): Bohem på liv og død

- Hild Borchgrevink (Dagsavisen): Opera som kunstig liv

- Kulturspeilet (Kjell Moe): En ny bohem - en ny tid

- Henning Høholt (Kulturkompasset): Rodolfo's dream – Herheims La Boheme in Oslo (in Norwegian)

The production

Composer: Giacomo Puccini

Libretto: Giuseppe Giacosa / Luigi Illica

Conductor: Eivind Gullberg Jensen (2012), Kirill Karabits (2012), Antonino Fogliani (2014)

Stage direction: Stefan Herheim

Stage design and costumes: Heike Scheele

Dramaturgy: Alexander Meier-Dörzenbach

Light: Anders Poll

Rodolfo:

Diego Torre (2012, 2014)

Daniel Johansson (2012, 2014)

Mimì:

Marita Sølberg (2012, 2014)

Mariann Fjeld Olsen (2012, 2014)

Musetta:

Jennifer Rowley (2012)

Nina Gravrok (2012, 2014)

Eli Kristin Hanssveen (2014)

Marcello:

Vasilij Ladjuk aka Vasily Ladyuk (2012, 2014)

Yngve A. Søberg (2012, 2014)

Colline:

Giovanni Battista Parodi (2012)

Petri Lindroos (2012, 2014)

Marcell Bakonyi (2014)

Schaunard:

Espen Langvik (2012, 2014)

David Pershall (2012)

Håvard Stensvold (2014)

Death (Benoit, Parpignol. Alcindoro):

Svein Erik Sagbråten (2012, 2014)

Brenden Gunnell (2012)

Interviews

Peter Konwitschny: I do not consider myself a representative of the Regietheater

Alexander Meier-Dörzenbach: There is so much more than mere sentimentality to this great opera

Detlef Roth: Amfortas' Suffering is Germany's

Kasper Holten: Tannhäuser's Rome narrative is perhaps all fiction—but it is his best story ever

Lisbeth Balslev: You come to Bayreuth for the sake of art

Iréne Theorin: Isolde is incredibly intense, and that really suits me

Graham Clark: I just switched hobbies

Anne Evans: At the time I hadn’t realised what a powerful impact it made

Johanna Meier on Isolde, Bayreuth and Ponnelle

Lioba Braun on Brangäne, Bayreuth and Wagner

Stephen Gould: Tristan is the end of the line

Penelope Turing: "Heil dir, Sonne!" Meant Something in those Conditions

Daniel Slater: The creation of the self through love and death

Sharon Polyak on West-Eastern Divan Orchestra, Wagner in Israel, Bayreuth